|

|

|

|

Drug-resistant ‘superbug’ in U.S. is a wake-up call

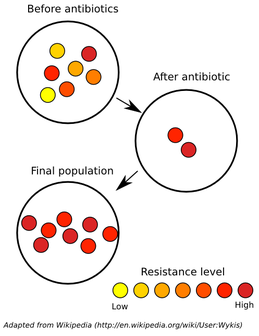

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention attributes 23,000 deaths to drug-resistant bacterial infections in the U.S. annually. Globally the number as high as 700,000 deaths. That number could rise to 10 million by 2050.

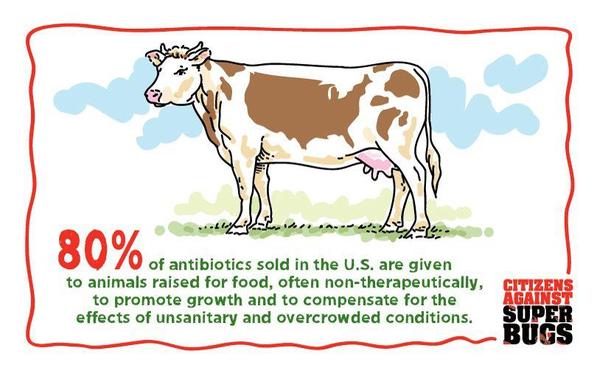

Factory farms have known of this threat for a long time but continued the practice of routinely giving animals antibiotics on a daily basis. They did it because after you kill good gut bacteria it throws off your metabolism and you gain weight faster. Meat producers love that. They also use a drug called ractopamine that accelerates the formation of muscle tissue and is given before slaughter to increase weight and profit. It can cripple an animal and starts a process that is not normal.

Antibiotics also needed daily because animals live in such horrific conditions they would otherwise easily die.

By giving antibiotics to cows and killing their gut bacteria they have increased carbon in the air and the warming of temperatures because the animal now is unable to break down food properly and creates more methane gas than a healthy cow that has not been given antibiotics.

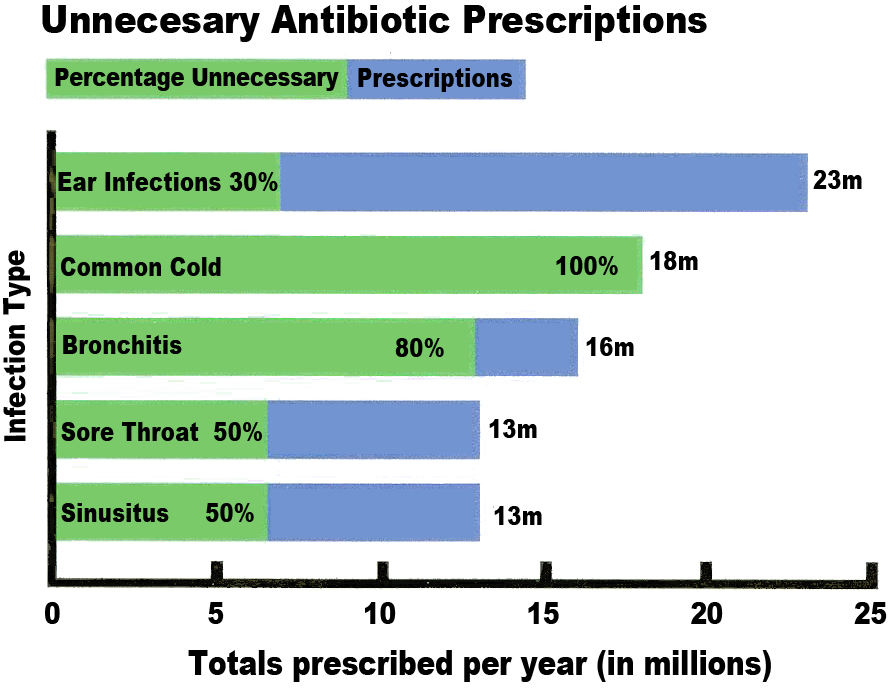

Doctors also routinely prescribe them to humans even if not needed, and then patients don't take the full prescription so the most resistant survive and then start to multiply in the person and cause a relapse or set up a scenario to pass it on to someone else. Condition can be a virus and not a bacterial infection so won't even help.

The sick are some of the most vulnerable to these bacteria and why the resistant show up and can run rampant in hospitals. Just when people need antibiotics to work the most.

Feel sick every time I see a commercial bragging they are not using them now, but still doing other things that are not acceptable and feeding cottonseed which is given the most toxic pesticides since not considered a food yet feeding to livestock, also use GMO corn/soy/cottonseed sprayed with cancer causing Roundup, arsenic and other drugs. These companies act like they deserve a prize when did it as long as they could get away with it and created this problem. Millions of chickens and pigs had to be killed due to viruses that spread throughout factory farms. Some turned their insides to mush. Instead these companies should pay for what they've done.

We tried to warn about this with a webpage explaining the process a few years ago. Can still see it under podcast tabs if not sure how it happens. There are other things being done to meat you may not know about such as bacteriophages on luncheon meats and gluing low cost cuts of meat together to make high cost cuts like filet mignon. Buy organic as these practices not allowed.

Go to the original article

Antibiotics also needed daily because animals live in such horrific conditions they would otherwise easily die.

By giving antibiotics to cows and killing their gut bacteria they have increased carbon in the air and the warming of temperatures because the animal now is unable to break down food properly and creates more methane gas than a healthy cow that has not been given antibiotics.

Doctors also routinely prescribe them to humans even if not needed, and then patients don't take the full prescription so the most resistant survive and then start to multiply in the person and cause a relapse or set up a scenario to pass it on to someone else. Condition can be a virus and not a bacterial infection so won't even help.

The sick are some of the most vulnerable to these bacteria and why the resistant show up and can run rampant in hospitals. Just when people need antibiotics to work the most.

Feel sick every time I see a commercial bragging they are not using them now, but still doing other things that are not acceptable and feeding cottonseed which is given the most toxic pesticides since not considered a food yet feeding to livestock, also use GMO corn/soy/cottonseed sprayed with cancer causing Roundup, arsenic and other drugs. These companies act like they deserve a prize when did it as long as they could get away with it and created this problem. Millions of chickens and pigs had to be killed due to viruses that spread throughout factory farms. Some turned their insides to mush. Instead these companies should pay for what they've done.

We tried to warn about this with a webpage explaining the process a few years ago. Can still see it under podcast tabs if not sure how it happens. There are other things being done to meat you may not know about such as bacteriophages on luncheon meats and gluing low cost cuts of meat together to make high cost cuts like filet mignon. Buy organic as these practices not allowed.

Go to the original article

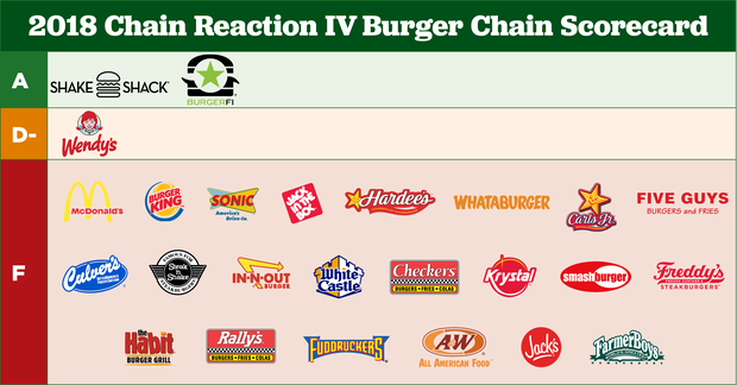

FAST FOOD CHAINS SCORE "F" FOR ANTIBIOTICS IN THEIR MEAT

Overuse of antibiotics in livestock can cause resistant bacteria to spread, putting humans at risk of developing life-threatening infections. The report says many meat producers give animals antibiotics to encourage quicker growth or stave off disease, calling it a routine practice.

"When antibiotics stop working, diseases become harder to treat, life-saving surgeries riskier to perform, and a scrape on the knee can even turn deadly," Jean Halloran, director of Food Policy Initiatives in the advocacy division of Consumer Reports, said in a news release Wednesday.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) calls antibiotic resistance "one of the biggest public health challenges of our time." The World Health Organization (WHO) calls it "one of the biggest threats to global health, food security, and development today."

"Each year in the U.S., at least 2 million people get an antibiotic-resistant infection, and at least 23,000 people die," the CDC says.

The WHO says antibiotic resistance is a natural occurrence accelerated by the misuse of antibiotics in both animals and humans.

GO TO THE FULL ARTICLE

"When antibiotics stop working, diseases become harder to treat, life-saving surgeries riskier to perform, and a scrape on the knee can even turn deadly," Jean Halloran, director of Food Policy Initiatives in the advocacy division of Consumer Reports, said in a news release Wednesday.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) calls antibiotic resistance "one of the biggest public health challenges of our time." The World Health Organization (WHO) calls it "one of the biggest threats to global health, food security, and development today."

"Each year in the U.S., at least 2 million people get an antibiotic-resistant infection, and at least 23,000 people die," the CDC says.

The WHO says antibiotic resistance is a natural occurrence accelerated by the misuse of antibiotics in both animals and humans.

GO TO THE FULL ARTICLE

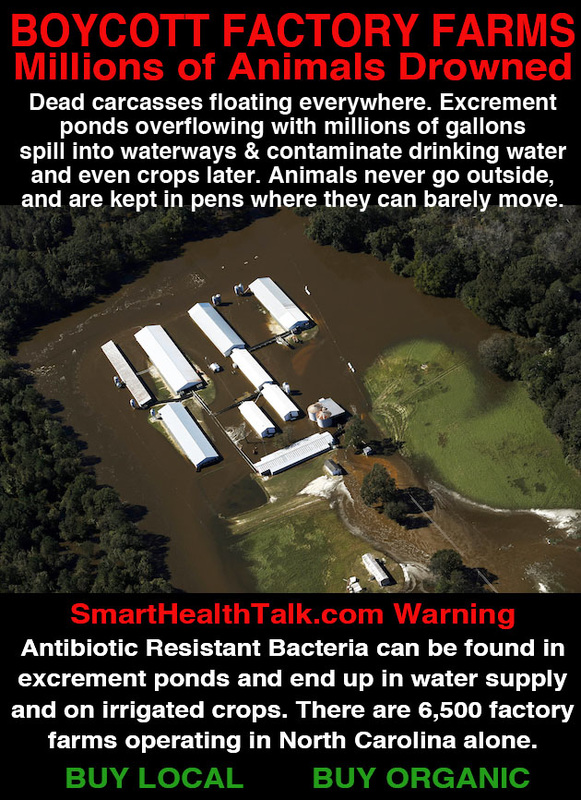

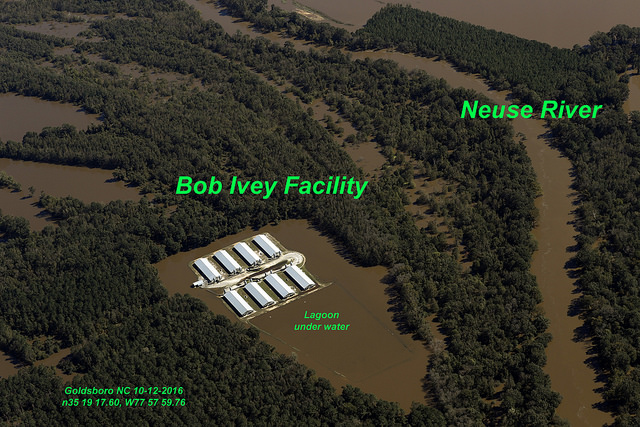

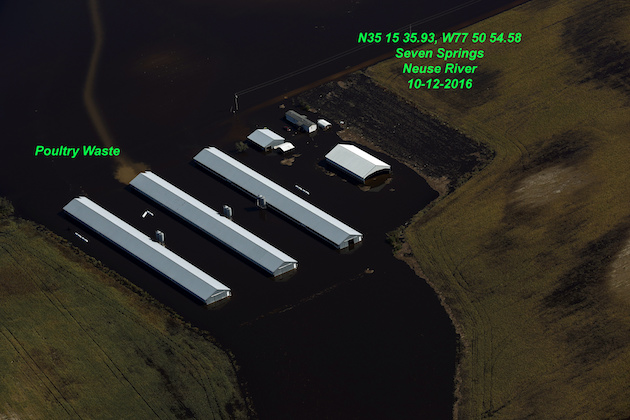

SMART HEALTH TALK WARNING THAT HURRICANE AND THOUSANDS OF FACTORY FARMS WITH EXCREMENT PONDS FULL OF MILLIONS OF GALLONS DON'T MIX

Spy Drones Expose Hidden Factory Farm in North Carolina. Matthew Wasn't the First Hurricane to Flood These Areas and Won't be the Last!

Follow a Spy Drone to see the hidden farms that are treating animals inhumanely and forcing consumers to be a part of their horrid operations. We have to turn to local organic farmers and stop buying these factory farmed meats.

Change will happen when consumers don't support these products and give their dollars to local organic farmers instead. This would not have happened if certain politicians that had something to benefit would not have gotten legislation passed that allowed loopholes that allow farms to keep expanding without having to meet environmental standards.

Say no to factory farmed food. Just because these farms are hidden behind trees and supporters in the right places, it is ultimately the consumer that allows these farms to exist, and it is the consumer that can easily put a stop to it when they say no with their dollars.

You can make a really great all organic grassfed burger at home for a meal that you eat out. Not that much work and health can also benefit. All those Omega 3s are a plus in addition to cutting out the pesticides that are programed to kill your cells. There is NO safe amount as it all does the same thing, kill cells. So which ones do you want to sacrifice?

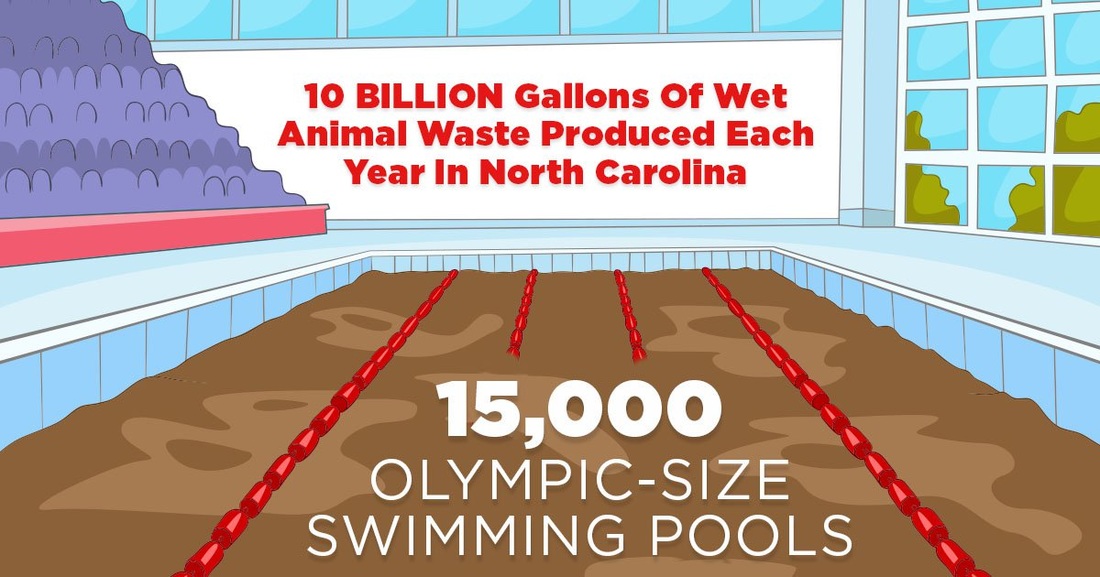

Using this factory model that has been replicated 6,500 times in North Carolina alone, cuts out the "humane tax." Because animals are raised as if feel no pain or suffering, costs can be cut. More product in less space so less operating money spent and more profit. This waiver of the "humane tax" saves the industry millions of dollars so now they can pad marketing budgets to fund commercials that sell us on eating the meat pumped out of these factories in all kinds of forms from a bacon cheeseburger, to breakfast burrito, to the bacon frying in a pan for breakfast. One third of the farms belong to SmithFields, which was purchased by a Chinese company Shuanghui International Holdings Ltd. Shuanghui Group in 2013.

With Hormel's purchase of Applegate Farms from company founders and General Mills deal with Organic Valley to make yogurt for one of their brands, we can be making it easier for them to buy out smaller companies so they can have a monopoly. our power for change is when we buy from organic, local farmers. Our health and our communities can greatly benefit from the extra business that can grow when money stays in the local economy and not in an off shore account.

Change will happen when consumers don't support these products and give their dollars to local organic farmers instead. This would not have happened if certain politicians that had something to benefit would not have gotten legislation passed that allowed loopholes that allow farms to keep expanding without having to meet environmental standards.

Say no to factory farmed food. Just because these farms are hidden behind trees and supporters in the right places, it is ultimately the consumer that allows these farms to exist, and it is the consumer that can easily put a stop to it when they say no with their dollars.

You can make a really great all organic grassfed burger at home for a meal that you eat out. Not that much work and health can also benefit. All those Omega 3s are a plus in addition to cutting out the pesticides that are programed to kill your cells. There is NO safe amount as it all does the same thing, kill cells. So which ones do you want to sacrifice?

Using this factory model that has been replicated 6,500 times in North Carolina alone, cuts out the "humane tax." Because animals are raised as if feel no pain or suffering, costs can be cut. More product in less space so less operating money spent and more profit. This waiver of the "humane tax" saves the industry millions of dollars so now they can pad marketing budgets to fund commercials that sell us on eating the meat pumped out of these factories in all kinds of forms from a bacon cheeseburger, to breakfast burrito, to the bacon frying in a pan for breakfast. One third of the farms belong to SmithFields, which was purchased by a Chinese company Shuanghui International Holdings Ltd. Shuanghui Group in 2013.

With Hormel's purchase of Applegate Farms from company founders and General Mills deal with Organic Valley to make yogurt for one of their brands, we can be making it easier for them to buy out smaller companies so they can have a monopoly. our power for change is when we buy from organic, local farmers. Our health and our communities can greatly benefit from the extra business that can grow when money stays in the local economy and not in an off shore account.

WHAT A MESS. MILLIONS OF DEAD ANIMALS AND ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANT BACTERIA SPREAD ALL OVER. IN WATER AND ON CROPS. EXCREMENT SPRAYED DIRECTLY ON SOIL. NOT COMPOSTED SO HEATED AND BACTERIA CAN BE KILLED.

We saw this coming last August when the Environmental Working Group (EWG) released their new tool for all of the factory farms in North Carolina and at the same time word that a hurricane could hit was a big red flag of what could be especially since it did happen before.

NORTH CAROLINA FACTORY FARMS EXPOSED!

GO TO THE ENVIRONMENTAL WORKING GROUP WEBSITE TO SEE DRONE VIEWS OVER 7,000 FACTORY FARMS THAT COVER THE STATE. ANIMALS NEVER SEE THE LIGHT OF DAY BUT ARE KEPT INSIDE THEIR ENTIRE LIVES.

CHICKENS, PIGS, DUCKS.

Scroll down to view interactive maps. Find the dark red "Sampson and Duplin County" where together they are producing 4 BILLION GALLONS OF WET EXCREMENT YEARLY THAN CAN BE CONTAMINATED WITH ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANT BACTERIA THAT CAN END UP IN WATERWAYS!

Dr. Michael Hansen, Sr. Scientist Consumers Union explains how there is research to show how deadly antibioitic resistant strains of E. Coli and Salmonella could be transferred from excrement pond, to waterway/river, to irrigation equipment, and then to produce that is sold to the consumer.

Applegate obviously fits right in with their other line of foods that care less if people eat toxic pesticides, GMOs, or animals treated humanely. NOT! We believe that after millions of animal deaths due to an epidemic of viruses that left egg supplies at the lowest since the 1930s. Factory farms are creating antibiotic resistant bacteria. They are afraid of another outbreak and organic Applegate was their backup plan and a source of "clean meat/animals."

Our enthusiasm for purchasing and supporting Applegate has changed and choose to NOT support Hormel Foods so have found other organic meat suppliers.

|

If you've had concerns about the safety of your meat, you'll want to ear what Steve McDonnell, CEO and Founder Applegate Farms Organic Meats has to say about antibiotics, GMOs, pink slime, nitrates and other meat additives, "natural" on the label, farm animal environmental contamination, feeding and housing practices, bringing back the family farm, and what high quality organic meats versus conventionally raised meats that use antibiotics daily in food is to eat. Conventional meat companies refuse interviews, where Steve was excited to join us and share information.

|

Steve McDonnell, CEO and founder of Applegate Farms, largest producer of processed organic meats in the USA, provided some great advice on choosing which meat is safest to purchase for our family, can deliver on taste that satisfies, and reevaluating how we budget meat. |

Since Chinese company Shuanghui now owns Smithfield they can feed their country without having to pollute it. Instead the billions of gallons of excrement produced by factory farms owned by the company can pollute the USA instead.

|

|

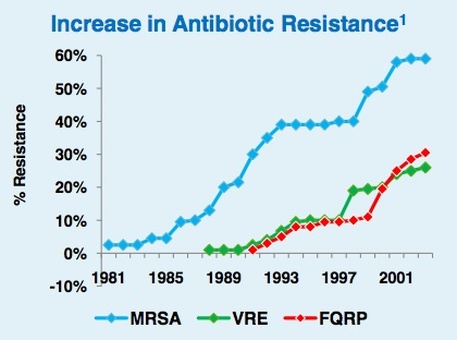

Antibiotic resistant bacteria are being formed at a higher rate than ever before, and being are dying from them at a higher rate than ever before.

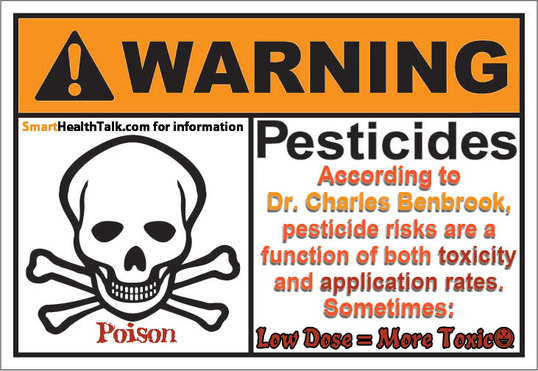

Pests and weeds are becoming resistant to pesticides and the chemical manufacturer's answer is new, stronger, more toxic options that FDA is approving for use.Pinterest Fan?So are we! Here is a pin from our GMO Posts board. Also suggest following other popular boards:

Weight Loss Meals & Tools, Favorite Meals, Vegan, Healing Tools, Special Treats, Gardening, Beverages, Alcoholic Drinks, Raw, Paleo, Vegetarian Meals, Most Important For Health All Smart Health Talk Approved!

|

Doctors Take Aim at Antibiotic Resistance From Factory Farming Operations That Use Antibiotics Dailyby Lynne Peeples

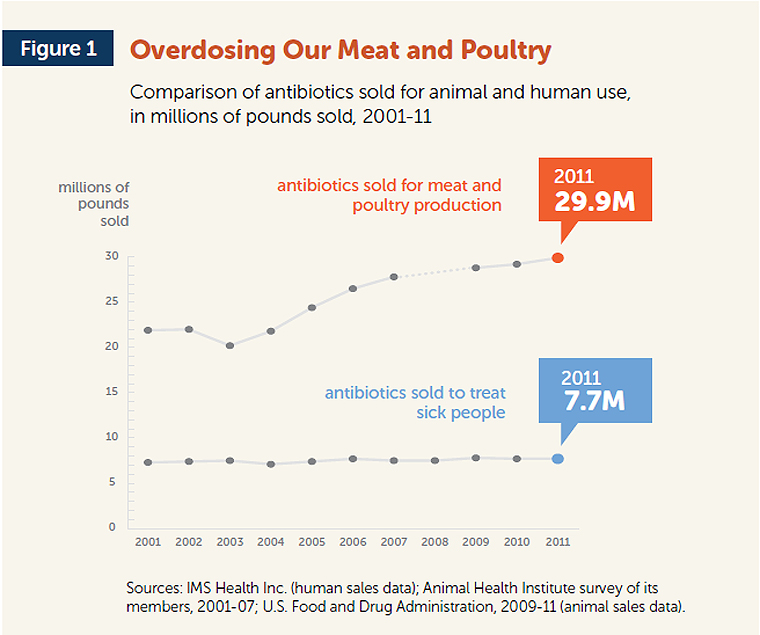

Huffington Post "Here's the big secret that no one wants to talk about: We're not very good at keeping what's inside a cow's intestines out of the meat." The roomful of young doctors at Oakland Children's Hospital chuckled as retired cardiologist Jeff Ritterman whispered audibly, his hand hiding his mouth. He went on to explain in less dramatic fashion how the widespread use of antibiotics to treat sick livestock, prevent the spread of disease in cramped conditions or simply promote animal growth has fueled the proliferation of antibiotic-resistant bacteria that is now making many infections in humans harder to treat. Some human infections now resist multiple antibiotics; the pathogens include methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a pathogen responsible for taking more lives each year than AIDS. Earlier this month, stores and consumers across the country discarded 36 million pounds of ground turkey in the second-largest recall in U.S. history. More than 100 people became sick from the salmonella-tainted meat; at least one person died. The firms feeding animals antibiotics question direct links to such outbreaks, but these kinds of tragedies come as little surprise to the medical community, which has long been confronted with the consequences of antibiotic resistance. "Everyone has seen cases of MRSA. Every doctor is schooled in how many seconds to wash their hands, and nurses are told to get rid of their nails," Ritterman, now a city councilmember in Richmond, Calif., told The Huffington Post. "It's a helpless feeling when your patient dies of an infection that you can't cure." More than 75 years after antibiotics first debuted as the miracle cure, treating an infection today often requires greater doses, a second drug or even riskier options. "Antibiotics are probably as big of an advance in medicine as there has ever been," Ritterman said. "We are undoing our greatest achievement." Eating contaminated meat is not the only route to an antibiotic-resistant infection. Contact with animals, meat or milk -- and even exposure to bacteria via the air or water -- can pose a public health threat. Of course, blame has also long been directed at the widespread use of antibiotics within medicine. Doctors have begun limiting the antibiotic prescriptions they write, aware that misuse or overuse of the drugs enables antibiotic-resistant bacteria to proliferate faster than their antibiotic-susceptible counterparts. In other words, what doesn't kill them makes them stronger -- potentially turning them into "superbugs" that can outsmart medicine's current range of weaponry. But while most doctors are familiar with the growing threat of antibiotic resistance, fewer are aware of the shared responsibility of agribusiness. "That part of the antibiotic resistance story is largely hidden for docs," said Ritterman, adding that he was shocked upon first hearing that 80 percent of the nation's antibiotics go to livestock. Doctors are learning, though, thanks partly to programs like the one at which Ritterman spoke, as well as a growing number of environmental health workshops and online modules. More clinicians now know, for example, that antibiotics approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for growth promotion in the early 1950s remain a huge part of the nation's livestock industry even though the government acknowledged the attendant health risks to humans more than 30 years ago. According to the FDA, about 90 percent of the antibiotics consumed by livestock are given to them via animal feed or water. Critics suggest that most of these drugs are used at low doses to bulk up the animals, speeding them to market. Exposure to antibiotics at levels insufficient to kill the bacteria are more likely to result in antibiotic resistance. Many in the food-animal production business beg to differ. Richard Carnevale, vice president for regulatory, scientific and international affairs at the Animal Health Institute, which represents pharmaceutical companies, argued that using the drug in the feed doesn't necessarily mean that it is being used "sub-therapeutically". "We don't really think that the antibiotics given to animals in feed are big contributors to the problems in human medicine," Carnevale said. Nearly half of the antibiotics used in agriculture, he said, are not even part of human medicine's antibacterial arsenal. "Antibiotics are used to keep animals as healthy as possible, and healthy animals are at the base of a safe food system," said Carnevale. He added that U.S. producers are "always looking for ways to change the way they do things to improve animal health," but that removing antibiotics would "increase production costs." While the battle wages in the United States, other countries including the entire European Union have banned the use of antibiotics for livestock growth promotion. The industry appears to be holding up just fine as resistance rates drop, according to recent Danish studies. Further, a U.S. study published last week in Environmental Health Perspectives found that going organic and stopping the use of antibiotics resulted in quick and significant reductions in antibiotic resistance. Lucia Sayre, co-executive director at the San Francisco Bay Area chapter of the advocacy groupPhysicians for Social Responsibility, says tapping the power and respect of the medical community can provide the necessary boost to change the food industry. "Nobody believes anyone more than their docs and nurses," Sayre said, citing a recent Gallup Poll that found 70 percent of people trusted their doctor's advice without a second opinion. "We're trying to max their voice." And when physicians and nurses realize that efforts in the doctor's office are not enough, she added, many -- like Ritterman, the retired cardiologist -- are eager to be vocal, whether educating patients and fellow doctors or advocating for regulatory reforms. "A doctor may be able to help individuals in their office, but changes in policy can lift the health of an entire population. We need to really advance American medicine to the policy stage," Ritterman said. "Doctors are trained to see the world through a health lens. Politicians, businessmen and economists are not." Entire hospitals are also in on the effort. Many have adopted the concept of "Meatless Mondays" -- using the money they save on Monday to buy grass-fed meat for Tuesday, for example. Many offer a variety of alternative sources of protein such as tofu and lentils. Fletcher Allen Health Care in Burlington, Vt., serves an estimated 2 million meals a year to patients, visitors and employees. Among other healthy improvements to their menu, they have been phasing out foods produced with non-therapeutic antibiotics antibiotics. Today, about 90 percent of their beef meets this goal. "I kept seeing more and more cases of antibiotic resistance at the hospital. It doesn't make sense to keep doing it the way we're doing it, not to mention that cases of resistance are costly," said Diane Imrie, director of nutrition services at Fletcher Allen. A study published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases in 2009 found that antibiotic-resistant infections cost U.S. hospitals more than $20 billion annually. Food and beverages mean big business in the health care sector, totaling about $14 billion a year. "Through a combination of clinicians talking to patients about personal choices and getting institutional purchasers like hospitals on board, I believe we can really change the food system," said Sayre, who helps coordinate a healthy-food campaign that includes nearly 350 hospitals, including Fletcher Allen. Sayre has also helped coordinate physicians in their push for new federal environmental health legislation. More than 1,000 signatures have been collected for the Preservation of Antibiotics for Medical Treatment Act, introduced in March after getting buried in Congress in 2007 and 2009. Another 378 groups have now endorsed the bill, including the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics. "Antibiotics are one of the most useful and important medical advances in recent history. Their effectiveness, however, is being compromised by bacterial resistance, arising in part from excessive use of antibiotics in animal agriculture," wrote Michael D. Maves, executive vice president of the association, in a letter of support for the legislation. Meanwhile, the FDA has issued a draft of "Guidance on the Judicious Use of Medically Important Antimicrobial Drugs in Food Producing Animals." The agency is currently reviewing comments and determining next steps, according to FDA spokeswoman Stephanie Yao, who said that while there is no estimated timeframe for implementing final recommendations, the agency is making it a priority. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also puts the issue "among its top concerns." And in June, a U.S. Department of Agriculture contractor reviewed the science and concluded that there is a strong link between rising cases of resistant infections and antibiotic use on factory farms. But as Mother Jones reported at the end of July, the "blunt" report disappeared shortly after it was posted on the Internet. (The Union of Concerned Scientists managed to recover a cached link.) A USDA spokesman said that the document had been "removed because it was published without the review required by USDA departmental regulations to ensure objectivity, accuracy, reliability and an unbiased presentation." Yet Mother Jones pointed to an earlier Dow Jones story that quoted a USDA spokesperson saying that the more than 60 studies compiled in the report were all from "reputed, scientific, peer-reviewed and scholarly journals." As the U.S. government stalls, other countries are moving ahead. Denmark, the world's leading exporter of pork, began phasing out non-therapeutic use of antibiotics more than 15 years ago. And empirical evidence suggests that the pigs are at least as healthy as ever, according to Frank M. Aarestrup, the head of the European Union Reference Laboratory for Antimicrobial Resistance and a member of the World Health Organization Collaborating Center for Antimicrobial Resistance in Foodborne Pathogens at the National Food Institute. "An early 'unscientific' estimate from the Danish agricultural industry identified increased mortality and reduced growth in piglets, while poultry and slaughter pigs were completely unaffected," Aarestrup, who is based at the Technical University of Denmark, wrote in an email. "More recently we have made a more thorough scientific analysis of the effects on the productivity and basically found no or in fact perhaps even a positive effect of the restriction." AHI, the pharma lobbying group, sides with the initial analysis of Denmark’s antibiotic use. "The data doesn't show any indications that they’ve had any impact on patterns or levels of human resistance," Carnevale said. "It's also clear that animal health has been negatively impacted. The use of antibiotics to treat disease has more than doubled as a result of health problem had in animals." "There was unfortunately no systematic monitoring in humans before the restrictions. Thus without a baseline it is difficult to give hard facts," Aarestrup conceded. "At least we have documented a major effect on reducing resistance in food animals and food products." Many U.S. experts on antibiotic resistance are frustrated that it has taken their country so long to take action. The FDA expressed their concern regarding the severity of the problem as early as the 1970s, and Ellen Silbergeld, a professor at Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, suggested that the dangers have been obvious for far longer. In 1945, upon accepting his piece of the Nobel Prize in Medicine for the discovery and isolation of penicillin, Scottish biologist Alexander Fleming delivered an ominous warning. "The time may come when penicillin can be bought by anyone in the shops. Then there is the danger that the ignorant man may easily underdose himself and, by exposing his microbes to non-lethal quantities of the drug, make them resistant," said Fleming, who had observed antibiotic resistance in his lab. His warning went largely unheeded. Soon after, the FDA approved use of the drugs in livestock feed, and the effectiveness of penicillin quickly plummeted. In a May 2011 lawsuit filed against the FDA for failing to curtail antibiotic use in animal feed, the plaintiff, the National Resources Defense Council, an environmental advocacy group, cited research suggesting that nearly half of the meat and poultry products in the U.S. contained drug-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus -- of which more than half were resistant to multiple classes of antibiotics. It is "all about the genes," Silbergeld said. "Bacteria are much smarter than we are. We should be thinking of them as masters of cloud computing, as they can access the entire genetic knowledge within their species." When a person is treated for an infection by a strain of pathogenic bacteria, Silbergeld said, the bacterial target of treatment has access to the entire bacterial community in the gut and its genetic resources for resisting antibiotics. This sharing, or "horizontal transfer" of genes, is highly efficient. As a result, she said, bacteria that had never been exposed to antibiotics could become resistant to them. Even the genes that bestow drug resistance to some sexually transmitted gonorrhea infections can be found in E. coli and other bacteria of the intestinal tract, noted Stuart Levy, a Tufts University microbiology professor who focuses on antibiotic resistance. The first “superbug” strain of a sexually transmitted disease was reported in July, after researchers discovered that none of the currently recommended treatments would kill the bacteria. "Gonorrhea didn’t invent its own resistance," Levy said. "It picked it up from other bacteria thanks to the misuse of antibiotics." Yao, the FDA spokeswoman, said the public health issue is further compounded by "the fact that the development of new antimicrobial drugs is not keeping pace with newly emerging drug-resistant pathogens." Newer sources of antibiotics are harder to find and therefore not always cost-effective for the pharmaceutical industry to pursue. Drugmakers acknowledge this shortfall. "The clinical need for new antibiotics is reaching crisis level, yet the antibiotic pipeline is running dry and fewer and fewer companies are working to develop drugs in this space," Elias Zerhouni, president of global research and development for the France-based pharmaceutical company Sanofi, said in a statement. "New approaches will be essential if we are to keep ahead of the resistance problems, and they will require a regulatory and business environment that is both public health and market driven that encourages risk–taking and rewards success," Eric Utt, director of medical and science policy at Pfizer wrote in an email. This effort may be all the more urgent if the political resistance to continues to stymie reform efforts. Public health experts say they hope the influence of the medical community will help advance regulation. "It's wonderful that physicians are looking at this," said Silbergeld. "Anything that can get the word out about the nature of this real crisis we're in, including the loss of efficacy of our drugs, is crucial." "At the end of the day," Ritterman said, "determining our policy by what's healthiest for humans, which is also healthiest for animals and the planet, will move us away from a trajectory of destruction and towards one of restoration and nourishment." Additional reporting by Robin Wilkey |

Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Problem Worsened By Human Abuse of Drugs

|

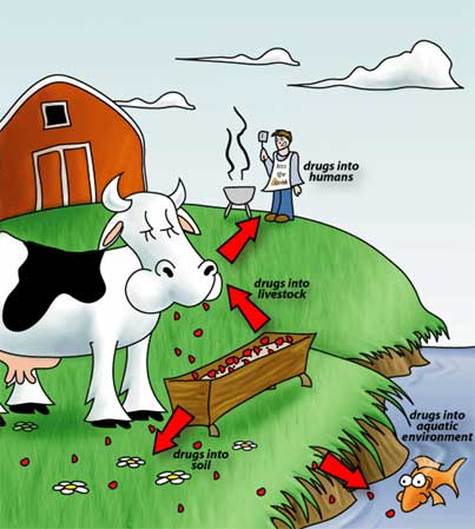

Antibiotics Don't Just Go Away

Click for article: "Contaminated Water From Medicine Threatens Wild Fish Populations, Study Shows" |

Antibiotics are available for purchase over the counter at feed stores for use without a prescription and absolutely no regulations.

|

We are feeding so much antibiotics to farm animals that the resistant bacteria will make it impossible for the drugs to work with humans and animals because the bacteria will not die.

Will the worst bird flu outbreak in US history finally make us reconsider factory farming chicken?

The outbreak has required that farmers resort to fire-extinguisher foam to kill off infected flocks. Can commercial farms protect themselves, or is US chicken farming fundamentally unsustainable?

Chicken farmer Craig Watts walks though a chicken house looking for dead and injured birds at C&A Farms in Fairmont, North Carolina. Industrial chicken farms have been hit hard by bird flu this year, prompting questions about how farming practices contribute to the disease’s spread. Photograph: Randall Hill/Reuters

The avian flu outbreak that has more than doubled egg prices across the country has also led to the death of more than 48 million birds in a dozen states, according to the US Department of Agriculture.

Iowa, the hardest hit, has euthanized more than 31 million birds, including approximately 40% of the state’s 60 million laying hens, according to Randy Olson, executive director of the Iowa Poultry Association. Turkey farmers in the state, while affected to a lesser degree, also have suffered. Minnesota, the leading turkey producer, has lost nearly 9 million turkeys.

The massive challenge of disposing of these sick birds illustrates the scale of chicken farming in the US. When avian flu infects a single bird on a chicken farm, the whole population has to be destroyed in order to stop the spread. In Iowa, for example, where an egg farm holds anywhere from 70,000 to 5 million birds, infection means slaughtering an unimaginable number of animals.

“It’s reasonable when we see these outbreaks to wonder if they are a manifestation of the unsustainability of the system,” says Suzanne McMillan, senior director of the farm and animal welfare campaign at the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA). “Bird flu is a window into how today’s poultry flocks live day to day, in intensive confinement and unsanitary conditions. It’s an unnatural, unsustainable situation.”

When an infected bird is detected on a farm, it is immediately quarantined and the USDA works in conjunction with the farmer to determine the best method for disposing of the exposed flock. “It is important to realize that each [avian influenza] outbreak incident is unique and involves site specific conditions that need to be considered in making the best disposal decision for the situation at the site,” reads a 2006 paper by the Environmental Protection Agency.

The reality is often much more emotional than that language might imply. “These farmers spend their entire careers caring for their animals and to see the disease affect their flocks … is an emotionally devastating event,” Olson says.

For egg-producing chickens, the majority of which are housed in cages, euthanasia by carbon-dioxide gas is the only method approved by the USDA.

Meanwhile for turkeys and broiler chickens, which are floor-reared (ie not kept in cages), the use of water-based foam similar to that used by firefighters is the most effective way to euthanize a large flock in a short period of time, says Beth Carlson, North Dakota’s deputy state veterinarian.

Approved for use by the USDA in 2006, the water-based foam suffocates the birds, which are typically herded into an enclosed area of the barn so that the foam can be deployed more quickly.

The foam’s active ingredient, propylene glycol, breaks down “relatively quickly (within several days to a week) in surface water and in soil”, according to the US Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease. The foaming agent, lauryl alcohol, is acutely toxic to marine animals, but has been deemed harmless to human health.

AdvertisementThe administration of the foam – either by nozzle or, more commonly for commercial farms, a foam generator – is a rolling process, meaning workers apply foam to birds at one end of the house, and then work their way, contained area by contained area, to the opposite end.

The foam needs to be six to 10 inches higher than the birds in order to suffocate them. Pumping in enough foam to cover their heads can take up to an hour.

“Individual birds are only exposed for a matter of seconds,” says Dr Eric Benson, a professor in the University of Delaware’s animal and food sciences department, who co-authored a paper on mass euthanasia methods for poultry. He says animals typically die within a minute.

In April, two turkey farms in North Dakota were infected and more than 100,000 birds euthanized as a result. Both farms used water-based foam.

“Euthanasia is never a pleasant thing to have to do,” Carlson says. But foam “is fast and minimally stressful for the birds, which means it’s less stressful for the people involved”.

Not all agree that using foam is humane. “We could do better,” says Michael Blackwell, chief veterinary officer at The Humane Society of the United States, who likens death by foam to “cuffing a person’s mouth and nose, during which time you are very much aware that your breathing has been precluded”.

Unlike Benson, he estimated that average death takes between three and seven minutes: “For any animal, that would be distressing.”

For floor-reared flocks, euthanasia by water-based foam is the cheapest and most efficient method available, as open-air barns do not need to be covered and the application requires fewer people to administer. And yet, says Blackwell, it is possible for farmers to use more humane alternatives by tarping floor-reared animals and administering inert gases, such as nitrogen and argon, which cause the birds to drift off, as if going to sleep.

Based on the size of the flock and local conditions, the dead birds are composted on-site (either indoors or outdoors), composted off-site, buried, moved to landfills or incinerated. Composting – in which dead birds are laid in rows, mixed with a bulking agent such as wood chips or saw dust and then left for approximately 30 days – is the preferred method of disposal, Benson says, because the virus is killed by the heat produced as the birds decompose. The problem with landfills, according to Benson, is that the virus might contaminate the soil or groundwater.

From backyard birds to commercial flocksThe avian influenza outbreak, which originated from the droppings of waterfowl carrying the virus, is showing signs of tapering off as temperatures continue to rise across the country. The virus is weakened by warm, dry conditions.

“The number of infections has certainly slowed in Iowa,” Olson says. “We are hopeful that this current outbreak is near its end.”

However, experts predict that the virus will return in the fall, when cooler, damp weather provides favorable conditions for its spread, and as ducks and other waterfowl complete reverse migration patterns.

While a report from the USDA, which investigated 80 commercial poultry farms, “cannot at present point to a single statistically significant pathway” for the spread of the outbreak, it determined that “a likely cause of some virus transmission is insufficient application of recommended biosecurity practices”.

The USDA report went on to recommend that all equipment and vehicles, as well as workers’ clothing, be disinfected before moving between farms.

“We need to learn lessons from this outbreak and modify biosecurity practices to minimize future outbreaks,” says Olson, citing a lack of consistency in the industry when it comes to auditing avian health hazards, as well as a need for more comprehensive guidelines for vehicle disinfection, as areas that require stricter standards. “This disease does not discriminate. We’ve seen it in backyard flocks; we’ve seen it in wild birds; we’ve seen it all types of commercial housing.”

Hon S Ip, a virologist at the US Geological Survey’s National Wildlife Health Center, disagrees with this assessment. During the initial outbreak starting in December, the disease was detected mainly in wild flocks in the Pacific Flyaway, a bird migration path from Alaska to Patagonia. But “in the Midwest there have been more commercial flocks infected than backyard flocks,” he says.

An ‘unsustainable system’This is likely, at least in part, because sunshine and warm backyard temperatures are effective at killing the virus, says Dr Michael Greger, director of public health and animal agriculture for the Humane Society of the United States.

Commercial poultry farms, on the other hand, “are designed like a disease incubator”, thanks to dark, moist and crowded conditions.

While factory poultry are more isolated, “when infected, [factory-farmed birds] are subject to wildfire-like outbreaks”, says Michael Davis, author of The Monster at Our Door: The Global Threat of Avian Flu.

On top of that, the genetic makeup of birds found in factory farms is often less diverse than those raised in backyard flocks. Due to the industry’s reliance on homogenous breeding techniques, commercially raised broilers are all pretty much genetically identical. Broilers and turkeys are artificially selected and bred to produce birds that grow quickly – at a rate 300% faster than those birds raised in 1960, according to the ASPCA – and produce as much breast protein as possible, to the point where the birds have a hard time standing upright.

Not only do commercial flocks share a limited gene pool, but some studies have suggested the industry’s vise-like focus on breast meat, in the case of broilers and turkeys, and eggs, in the case of hens, suppresses the birds’ immune systems, a theory known as resource allocation.

When a bird is bred so that all its energy goes to the production of meat or eggs, “something has to give”, says the ASPCA’s McMillan. “The science indicates that a bird’s immunity goes down.”

As Greger puts it: “There is an inverse relationship between accelerated growth and disease resistance, which means faster-growing birds are more susceptible to illness.”

While the USDA terms this outbreak “a wake-up call on biosecurity”, the idea of hermetically sealing farms, which use ventilation fans to keep birds cool, may be too difficult to enforce. “The industrial poultry system, by its very nature, is vulnerable to these kinds of infections,” he says.

It’s the system that is at fault, according to McMillan. “We are forcing birds to live in unbalanced ways, both physically and genetically,”she says. Commercial poultry flocks “are bred to suffer. We force them to live a life of misery, and from that perspective, they are going to be more prone to contracting and spreading disease. These are not healthy, balanced animals.”

Iowa, the hardest hit, has euthanized more than 31 million birds, including approximately 40% of the state’s 60 million laying hens, according to Randy Olson, executive director of the Iowa Poultry Association. Turkey farmers in the state, while affected to a lesser degree, also have suffered. Minnesota, the leading turkey producer, has lost nearly 9 million turkeys.

The massive challenge of disposing of these sick birds illustrates the scale of chicken farming in the US. When avian flu infects a single bird on a chicken farm, the whole population has to be destroyed in order to stop the spread. In Iowa, for example, where an egg farm holds anywhere from 70,000 to 5 million birds, infection means slaughtering an unimaginable number of animals.

“It’s reasonable when we see these outbreaks to wonder if they are a manifestation of the unsustainability of the system,” says Suzanne McMillan, senior director of the farm and animal welfare campaign at the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA). “Bird flu is a window into how today’s poultry flocks live day to day, in intensive confinement and unsanitary conditions. It’s an unnatural, unsustainable situation.”

When an infected bird is detected on a farm, it is immediately quarantined and the USDA works in conjunction with the farmer to determine the best method for disposing of the exposed flock. “It is important to realize that each [avian influenza] outbreak incident is unique and involves site specific conditions that need to be considered in making the best disposal decision for the situation at the site,” reads a 2006 paper by the Environmental Protection Agency.

The reality is often much more emotional than that language might imply. “These farmers spend their entire careers caring for their animals and to see the disease affect their flocks … is an emotionally devastating event,” Olson says.

For egg-producing chickens, the majority of which are housed in cages, euthanasia by carbon-dioxide gas is the only method approved by the USDA.

Meanwhile for turkeys and broiler chickens, which are floor-reared (ie not kept in cages), the use of water-based foam similar to that used by firefighters is the most effective way to euthanize a large flock in a short period of time, says Beth Carlson, North Dakota’s deputy state veterinarian.

Approved for use by the USDA in 2006, the water-based foam suffocates the birds, which are typically herded into an enclosed area of the barn so that the foam can be deployed more quickly.

The foam’s active ingredient, propylene glycol, breaks down “relatively quickly (within several days to a week) in surface water and in soil”, according to the US Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease. The foaming agent, lauryl alcohol, is acutely toxic to marine animals, but has been deemed harmless to human health.

AdvertisementThe administration of the foam – either by nozzle or, more commonly for commercial farms, a foam generator – is a rolling process, meaning workers apply foam to birds at one end of the house, and then work their way, contained area by contained area, to the opposite end.

The foam needs to be six to 10 inches higher than the birds in order to suffocate them. Pumping in enough foam to cover their heads can take up to an hour.

“Individual birds are only exposed for a matter of seconds,” says Dr Eric Benson, a professor in the University of Delaware’s animal and food sciences department, who co-authored a paper on mass euthanasia methods for poultry. He says animals typically die within a minute.

In April, two turkey farms in North Dakota were infected and more than 100,000 birds euthanized as a result. Both farms used water-based foam.

“Euthanasia is never a pleasant thing to have to do,” Carlson says. But foam “is fast and minimally stressful for the birds, which means it’s less stressful for the people involved”.

Not all agree that using foam is humane. “We could do better,” says Michael Blackwell, chief veterinary officer at The Humane Society of the United States, who likens death by foam to “cuffing a person’s mouth and nose, during which time you are very much aware that your breathing has been precluded”.

Unlike Benson, he estimated that average death takes between three and seven minutes: “For any animal, that would be distressing.”

For floor-reared flocks, euthanasia by water-based foam is the cheapest and most efficient method available, as open-air barns do not need to be covered and the application requires fewer people to administer. And yet, says Blackwell, it is possible for farmers to use more humane alternatives by tarping floor-reared animals and administering inert gases, such as nitrogen and argon, which cause the birds to drift off, as if going to sleep.

Based on the size of the flock and local conditions, the dead birds are composted on-site (either indoors or outdoors), composted off-site, buried, moved to landfills or incinerated. Composting – in which dead birds are laid in rows, mixed with a bulking agent such as wood chips or saw dust and then left for approximately 30 days – is the preferred method of disposal, Benson says, because the virus is killed by the heat produced as the birds decompose. The problem with landfills, according to Benson, is that the virus might contaminate the soil or groundwater.

From backyard birds to commercial flocksThe avian influenza outbreak, which originated from the droppings of waterfowl carrying the virus, is showing signs of tapering off as temperatures continue to rise across the country. The virus is weakened by warm, dry conditions.

“The number of infections has certainly slowed in Iowa,” Olson says. “We are hopeful that this current outbreak is near its end.”

However, experts predict that the virus will return in the fall, when cooler, damp weather provides favorable conditions for its spread, and as ducks and other waterfowl complete reverse migration patterns.

While a report from the USDA, which investigated 80 commercial poultry farms, “cannot at present point to a single statistically significant pathway” for the spread of the outbreak, it determined that “a likely cause of some virus transmission is insufficient application of recommended biosecurity practices”.

The USDA report went on to recommend that all equipment and vehicles, as well as workers’ clothing, be disinfected before moving between farms.

“We need to learn lessons from this outbreak and modify biosecurity practices to minimize future outbreaks,” says Olson, citing a lack of consistency in the industry when it comes to auditing avian health hazards, as well as a need for more comprehensive guidelines for vehicle disinfection, as areas that require stricter standards. “This disease does not discriminate. We’ve seen it in backyard flocks; we’ve seen it in wild birds; we’ve seen it all types of commercial housing.”

Hon S Ip, a virologist at the US Geological Survey’s National Wildlife Health Center, disagrees with this assessment. During the initial outbreak starting in December, the disease was detected mainly in wild flocks in the Pacific Flyaway, a bird migration path from Alaska to Patagonia. But “in the Midwest there have been more commercial flocks infected than backyard flocks,” he says.

An ‘unsustainable system’This is likely, at least in part, because sunshine and warm backyard temperatures are effective at killing the virus, says Dr Michael Greger, director of public health and animal agriculture for the Humane Society of the United States.

Commercial poultry farms, on the other hand, “are designed like a disease incubator”, thanks to dark, moist and crowded conditions.

While factory poultry are more isolated, “when infected, [factory-farmed birds] are subject to wildfire-like outbreaks”, says Michael Davis, author of The Monster at Our Door: The Global Threat of Avian Flu.

On top of that, the genetic makeup of birds found in factory farms is often less diverse than those raised in backyard flocks. Due to the industry’s reliance on homogenous breeding techniques, commercially raised broilers are all pretty much genetically identical. Broilers and turkeys are artificially selected and bred to produce birds that grow quickly – at a rate 300% faster than those birds raised in 1960, according to the ASPCA – and produce as much breast protein as possible, to the point where the birds have a hard time standing upright.

Not only do commercial flocks share a limited gene pool, but some studies have suggested the industry’s vise-like focus on breast meat, in the case of broilers and turkeys, and eggs, in the case of hens, suppresses the birds’ immune systems, a theory known as resource allocation.

When a bird is bred so that all its energy goes to the production of meat or eggs, “something has to give”, says the ASPCA’s McMillan. “The science indicates that a bird’s immunity goes down.”

As Greger puts it: “There is an inverse relationship between accelerated growth and disease resistance, which means faster-growing birds are more susceptible to illness.”

While the USDA terms this outbreak “a wake-up call on biosecurity”, the idea of hermetically sealing farms, which use ventilation fans to keep birds cool, may be too difficult to enforce. “The industrial poultry system, by its very nature, is vulnerable to these kinds of infections,” he says.

It’s the system that is at fault, according to McMillan. “We are forcing birds to live in unbalanced ways, both physically and genetically,”she says. Commercial poultry flocks “are bred to suffer. We force them to live a life of misery, and from that perspective, they are going to be more prone to contracting and spreading disease. These are not healthy, balanced animals.”