There is no doubt the Chlorpyrifos pesticides are destroying the brains of our children which can start before they are even born. These toxic pesticides are being sprayed all around us and are used on our food. After the research summarized below as well as many other studies that verified these findings, the gov't was on track for stopping the use of Chlorpyrifos, but the Trump administration has reversed that and will allow their use to continue. Chemical industry influence and profits trumps protection of our children. Money and power can buy policy decisions and allow poisoning us all even though we have choices.

Go to the EWG link here or click here for link to PDF of Pediatrician/EWG letter.

On June 27, 2017, the American Academy for Pediatrics and EWG sent the letter attached and below to Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt on the agency's recent decision to pull back a scheduled ban on the pesticides chlorpyrifos.

--

June 27, 2017

Scott Pruitt

Administrator

Environmental Protection Agency

1200 Pennsylvania Ave. NW

Washington, DC 20460

Dear Administrator Pruitt:

The American Academy of Pediatrics is a nonprofit professional organization of 66,000 primary care pediatricians, pediatric medical specialists, and pediatric surgical specialists dedicated to the health, safety, and well-being of infants, children, adolescents, and young adults.

The Environmental Working Group is a nonprofit advocacy organization dedicated to protecting public health and the environment. EWG has a long history of advocating for safer chemical policies and reducing the use of dangerous pesticides like chlorpyrifos.

We are writing to express concern at the agency’s recent reversal on its proposal to revoke tolerances for chlorpyrifos. In particular, we are deeply alarmed that the EPA’s decision to allow the continued use of chlorpyrifos contradicts the agency’s own science and puts developing fetuses, infants, children, and pregnant women at risk.

Children are Uniquely Vulnerable to Risks from Pesticides

Children are not small adults – they have key neurological, physical, developmental, and behavioral differences from adults that make them uniquely vulnerable to chemical exposures. By size and weight, children drink more, breathe more, and have more skin surface area to body weight relative to adults, making their bodies more sensitive to pesticides and other chemicals. Their brains and nervous systems are still making connections and maturing, processes that are particularly sensitive to interference by pesticides. Children come into contact with pesticides daily through air, food, dust, and soil, and on surfaces through home and public lawn or garden application, household insecticide use, application to pests, and agricultural product residues.[1]

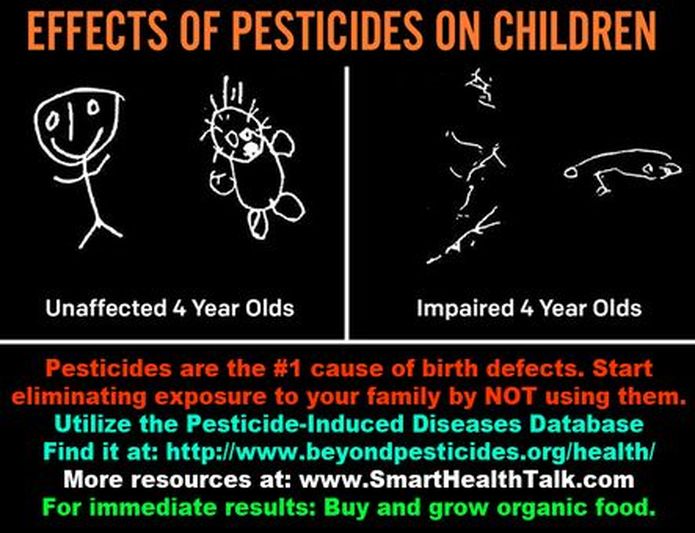

Epidemiologic studies associate pesticide exposure with adverse birth outcomes, including preterm birth, low birth weight, congenital abnormalities, pediatric cancers, neurobehavioral and cognitive deficits, and asthma. The evidence is especially strong linking certain pesticide exposure with pediatric cancers and permanent neurological damage. [2] Some birth cohort studies of American children have found associations between pesticide exposure and neurobehavioral and cognitive defects like lower IQs, autism, and attention deficit disorders.[3]

Chlorpyrifos Poses Specific Risks to Children

There is a wealth of science demonstrating the detrimental effects of chlorpyrifos exposure to developing fetuses, infants, children, and pregnant women. Like other organophosphate pesticides, chlorpyrifos interferes with enzymes in the nervous system. Symptoms in people acutely overexposed to chlorpyrifos can range from runny noses and drooling to nausea, vomiting, headaches, muscle cramps, and even loss of coordination. Severe poisoning can cause unconsciousness, convulsions, difficulty breathing, paralysis and death.[4]

Chronic chlorpyrifos exposure in utero is associated with changes in social behavior, brain development, and developmental delays.[5] A long-term Columbia University study following children born before and after a ban on in-home use of chlorpyrifos took effect found that the children born before the ban had much higher exposure levels, tended to be smaller, have poorer reflexes, and weigh less.[6] Toddlers with higher exposures were behind in both motor and mental development by age three. They were also greater than five times more likely to be on the autism spectrum, greater than six times more likely to have ADHD-type symptoms, and greater than 11 times more likely to have symptoms of other attention disorders.[7] The Columbia study[8] and similar long-term studies conducted at the University of California, Berkeley, and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City[9] found lower IQs for children with prenatal chlorpyrifos exposure.

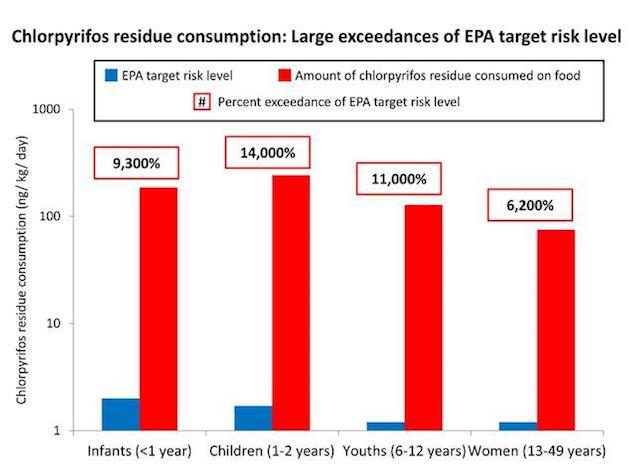

Children face unique exposure risks. EPA estimates that children ages 1 to 12 are exposed to significantly more chlorpyrifos through their diets per pound of body weight than adults.[10] Chlorpyrifos is authorized for use on nearly 50 food crops, including fruits, vegetables, and nuts. In annual tests for pesticide residues on conventionally grown produce, the U.S. Department of Agriculture found chlorpyrifos on commonly eaten fruits and vegetables, including in especially high concentrations on fruits like peaches and nectarines.[11]

Even low residues of exposures to neurotoxic pesticides such as chlorpyrifos contribute to aggregate risks. EPA’s own calculations suggest that babies, children and pregnant women all eat much more chlorpyrifos than is safe. EPA has estimated that median or “typical” exposures for babies are likely five times greater than its proposed “safe” intake, and 11 to 15 times higher for toddlers and older children. Pregnant women are also impacted – a typical exposure is five times higher than it ought to be to protect her developing fetus from harm.[12] EPA’s 2016 Risk Assessment found that chlorpyrifos causes harm to children’s brains from prenatal exposures, and that this harm occurs at levels far lower than EPA’s acute poisoning regulatory endpoint.[13]

EPA’s Decision Contradicts the Agency’s Science

The Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA) takes an explicitly precautionary approach to pesticide safety and children’s health. Under the FQPA, EPA must revoke permitted pesticide residue levels, or tolerances, if it determines those levels are no longer safe. Safe under the FQPA means that “there is a reasonable certainty that no harm will result from aggregate exposure to the pesticide chemical residue, including all anticipated dietary exposures and other exposures for which there is reliable information.”[14] Thus, while uncertainty about a pesticide’s safety can be the basis for removing tolerances, it cannot be the basis for continuing use of that pesticide and potentially exposing people to risk.

Additionally, EPA is required under the provisions of FQPA to give special consideration to in-utero exposures, and to children and infants, particularly with regards to neurological differences from adults, when evaluating pesticide safety. For that reason, the FQPA requires EPA to apply an additional tenfold safety factor to account for data gaps and potential pre- or postnatal toxicity to children.[15]

EPA has consistently found that chlorpyrifos is not safe, particularly in regard to in-utero exposure and exposures to children. In December 2014, EPA found unsafe drinking water contamination from chlorpyrifos as part of its risk assessment.[16] In October 2015, EPA proposed to revoke all tolerances because it could not determine that aggregate exposure to residues of chlorpyrifos were safe to children or the general population under the requirements of the FQPA.[17] In November 2016, EPA did yet another risk assessment using a more sensitive point of departure, determining the risks were even greater than previously thought and reiterating the need to revoke tolerances.[18]

We are deeply alarmed by EPA’s decision not to finalize the proposed rule to end chlorpyrifos uses on food – a decision that was premised on the need for further study on the effects of chlorpyrifos on children before finalizing a rule. EPA’s previous risk assessments and several consultations with EPA’s Science Advisory Panel makes clear the potential for adverse health effects to children as a result of exposure to chlorpyrifos. The risk to infant and children’s health and development is unambiguous. The clear statutory language of the FQPA requires that EPA revoke tolerances in the face of uncertainty. EPA has no new evidence indicating that chlorpyrifos exposures are safe. As a result, EPA has no basis to allow continued use of chlorpyrifos, and its insistence in doing so puts all children at risk.

We urge EPA to rely on the established science and to take action to revoke all tolerances for chlorpyrifos, as proposed in 2015. America’s children today and in the future deserve and demand no less.

Sincerely,

Fernando Stein, MD, FAAP

President American

Academy of Pediatrics

Ken Cook

President

Environmental Working Group

[1] American Academy of Pediatrics, Policy Statement: Pesticide Exposure in Children, 130 Pediatrics e1757, e1757-58 (2012), http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/130/6/e1757.ful...

[2] Id. at e1759-60.

[3] Id. at e1760.

[4] National Pesticide Information Center, Chlorpyrifos, http://npic.orst.edu/factsheets/chlorpgen.html (last visited April 13, 2017).

[5] Id.

[6] Virginia A. Rauh, ScD., Discussion of Analyses of Prenatal Chlorpyrifos Exposure and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes, Columbia School of Children’s Environmental Health, https://archive.epa.gov/scipoly/sap/meetings/web/pdf/rauh.pdf (last accessed April 13, 2007).

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] University of California Berkley, Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas (CHAMACOS), http://cerch.berkeley.edu/research-programs/chamacos-study (last visited April 13, 2017). See also Engel SM, Bradman A, Wolff MS, Rauh VA, Harley KG, Yang JH, Hoepner LA, Barr DB, Yolton K, Vedar MG, Xu Y, Hornung RW, Wetmur JG, Chen J, Holland NT, Perera FP, Whyatt RM, Lanphear BP, Eskenazi B. Prenatal Organophosphorus Pesticide Exposure and Child Neurodevelopment at 24 Months: An Analysis of Four Birth Cohorts. Environ Health Perspect. 2016 Jun;124(6):822-30. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1409474. Epub 2015 Sep 29. PubMed PMID: 26418669; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4892910. See also Engel SM, Wetmur J, Chen J, Zhu C, Barr DB, Canfield RL, Wolff MS. Prenatal exposure to organophosphates, paraoxonase 1, and cognitive development in childhood. Environ Health Perspect. 2011 Aug;119(8):1182-8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003183. Epub 2011 Apr 21. PubMed PMID: 21507778; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3237356.

[10] U.S. Environmental Protection Administration, Chlorpyrifos Acute and Steady State Dietary (Food Only) Exposure Analysis to Support Registration Review, EPA-HQ-OPP-2008-0850-0197 (Nov. 18, 2014), https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=EPA-HQ-OPP-2008-0850-0197.

[11] U.S. Dep’t of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service, Pesticide Data Program, https://www.ams.usda.gov/datasets/pdp (last visited April 13. 2017).

[12] U.S. Environmental Protection Administration, Chlorpyrifos Acute and Steady State Dietary (Food Only) Exposure Analysis to Support Registration Review, EPA-HQ-OPP-2008-0850-0197 (Nov. 18, 2014), https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=EPA-HQ-OPP-2008-0850-0197.

[13] U.S. Environmental Protection Administration, Chlorpyrifos: Revised Human Health Risk Assessment for Registration Review, EPA-HQ-OPP-2015-0653-0454 (Nov. 3, 2016), https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=EPA-HQ-OPP-2015-0653-0454.

[14] 21 U.S.C. § 346a(b)(2)(A)(ii).

[15] 21 U.S.C. § 346a(b)(2)(C).

[16] U.S. Environmental Protection Administration, Chlorpyrifos: Acute and Steady State Dietary (Food Only) Exposure Analysis to Support Registration Review, EPA-HQ-OPP-2008-0850-0197 (Nov. 18, 2014), https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=EPA-HQ-OPP-2008-0850-0197.

[17] 80 Fed. Reg. 69,080, 69,081 (Nov. 6, 2015).

[18] U.S. Environmental Protection Administration, Chlorpyrifos: Revised Human Health Risk Assessment for Registration Review, EPA-HQ-OPP-2015-0653-0454 (Nov. 3, 2016), https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=EPA-HQ-OPP-2015-0653-0454.

On June 27, 2017, the American Academy for Pediatrics and EWG sent the letter attached and below to Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt on the agency's recent decision to pull back a scheduled ban on the pesticides chlorpyrifos.

--

June 27, 2017

Scott Pruitt

Administrator

Environmental Protection Agency

1200 Pennsylvania Ave. NW

Washington, DC 20460

Dear Administrator Pruitt:

The American Academy of Pediatrics is a nonprofit professional organization of 66,000 primary care pediatricians, pediatric medical specialists, and pediatric surgical specialists dedicated to the health, safety, and well-being of infants, children, adolescents, and young adults.

The Environmental Working Group is a nonprofit advocacy organization dedicated to protecting public health and the environment. EWG has a long history of advocating for safer chemical policies and reducing the use of dangerous pesticides like chlorpyrifos.

We are writing to express concern at the agency’s recent reversal on its proposal to revoke tolerances for chlorpyrifos. In particular, we are deeply alarmed that the EPA’s decision to allow the continued use of chlorpyrifos contradicts the agency’s own science and puts developing fetuses, infants, children, and pregnant women at risk.

Children are Uniquely Vulnerable to Risks from Pesticides

Children are not small adults – they have key neurological, physical, developmental, and behavioral differences from adults that make them uniquely vulnerable to chemical exposures. By size and weight, children drink more, breathe more, and have more skin surface area to body weight relative to adults, making their bodies more sensitive to pesticides and other chemicals. Their brains and nervous systems are still making connections and maturing, processes that are particularly sensitive to interference by pesticides. Children come into contact with pesticides daily through air, food, dust, and soil, and on surfaces through home and public lawn or garden application, household insecticide use, application to pests, and agricultural product residues.[1]

Epidemiologic studies associate pesticide exposure with adverse birth outcomes, including preterm birth, low birth weight, congenital abnormalities, pediatric cancers, neurobehavioral and cognitive deficits, and asthma. The evidence is especially strong linking certain pesticide exposure with pediatric cancers and permanent neurological damage. [2] Some birth cohort studies of American children have found associations between pesticide exposure and neurobehavioral and cognitive defects like lower IQs, autism, and attention deficit disorders.[3]

Chlorpyrifos Poses Specific Risks to Children

There is a wealth of science demonstrating the detrimental effects of chlorpyrifos exposure to developing fetuses, infants, children, and pregnant women. Like other organophosphate pesticides, chlorpyrifos interferes with enzymes in the nervous system. Symptoms in people acutely overexposed to chlorpyrifos can range from runny noses and drooling to nausea, vomiting, headaches, muscle cramps, and even loss of coordination. Severe poisoning can cause unconsciousness, convulsions, difficulty breathing, paralysis and death.[4]

Chronic chlorpyrifos exposure in utero is associated with changes in social behavior, brain development, and developmental delays.[5] A long-term Columbia University study following children born before and after a ban on in-home use of chlorpyrifos took effect found that the children born before the ban had much higher exposure levels, tended to be smaller, have poorer reflexes, and weigh less.[6] Toddlers with higher exposures were behind in both motor and mental development by age three. They were also greater than five times more likely to be on the autism spectrum, greater than six times more likely to have ADHD-type symptoms, and greater than 11 times more likely to have symptoms of other attention disorders.[7] The Columbia study[8] and similar long-term studies conducted at the University of California, Berkeley, and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City[9] found lower IQs for children with prenatal chlorpyrifos exposure.

Children face unique exposure risks. EPA estimates that children ages 1 to 12 are exposed to significantly more chlorpyrifos through their diets per pound of body weight than adults.[10] Chlorpyrifos is authorized for use on nearly 50 food crops, including fruits, vegetables, and nuts. In annual tests for pesticide residues on conventionally grown produce, the U.S. Department of Agriculture found chlorpyrifos on commonly eaten fruits and vegetables, including in especially high concentrations on fruits like peaches and nectarines.[11]

Even low residues of exposures to neurotoxic pesticides such as chlorpyrifos contribute to aggregate risks. EPA’s own calculations suggest that babies, children and pregnant women all eat much more chlorpyrifos than is safe. EPA has estimated that median or “typical” exposures for babies are likely five times greater than its proposed “safe” intake, and 11 to 15 times higher for toddlers and older children. Pregnant women are also impacted – a typical exposure is five times higher than it ought to be to protect her developing fetus from harm.[12] EPA’s 2016 Risk Assessment found that chlorpyrifos causes harm to children’s brains from prenatal exposures, and that this harm occurs at levels far lower than EPA’s acute poisoning regulatory endpoint.[13]

EPA’s Decision Contradicts the Agency’s Science

The Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA) takes an explicitly precautionary approach to pesticide safety and children’s health. Under the FQPA, EPA must revoke permitted pesticide residue levels, or tolerances, if it determines those levels are no longer safe. Safe under the FQPA means that “there is a reasonable certainty that no harm will result from aggregate exposure to the pesticide chemical residue, including all anticipated dietary exposures and other exposures for which there is reliable information.”[14] Thus, while uncertainty about a pesticide’s safety can be the basis for removing tolerances, it cannot be the basis for continuing use of that pesticide and potentially exposing people to risk.

Additionally, EPA is required under the provisions of FQPA to give special consideration to in-utero exposures, and to children and infants, particularly with regards to neurological differences from adults, when evaluating pesticide safety. For that reason, the FQPA requires EPA to apply an additional tenfold safety factor to account for data gaps and potential pre- or postnatal toxicity to children.[15]

EPA has consistently found that chlorpyrifos is not safe, particularly in regard to in-utero exposure and exposures to children. In December 2014, EPA found unsafe drinking water contamination from chlorpyrifos as part of its risk assessment.[16] In October 2015, EPA proposed to revoke all tolerances because it could not determine that aggregate exposure to residues of chlorpyrifos were safe to children or the general population under the requirements of the FQPA.[17] In November 2016, EPA did yet another risk assessment using a more sensitive point of departure, determining the risks were even greater than previously thought and reiterating the need to revoke tolerances.[18]

We are deeply alarmed by EPA’s decision not to finalize the proposed rule to end chlorpyrifos uses on food – a decision that was premised on the need for further study on the effects of chlorpyrifos on children before finalizing a rule. EPA’s previous risk assessments and several consultations with EPA’s Science Advisory Panel makes clear the potential for adverse health effects to children as a result of exposure to chlorpyrifos. The risk to infant and children’s health and development is unambiguous. The clear statutory language of the FQPA requires that EPA revoke tolerances in the face of uncertainty. EPA has no new evidence indicating that chlorpyrifos exposures are safe. As a result, EPA has no basis to allow continued use of chlorpyrifos, and its insistence in doing so puts all children at risk.

We urge EPA to rely on the established science and to take action to revoke all tolerances for chlorpyrifos, as proposed in 2015. America’s children today and in the future deserve and demand no less.

Sincerely,

Fernando Stein, MD, FAAP

President American

Academy of Pediatrics

Ken Cook

President

Environmental Working Group

[1] American Academy of Pediatrics, Policy Statement: Pesticide Exposure in Children, 130 Pediatrics e1757, e1757-58 (2012), http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/130/6/e1757.ful...

[2] Id. at e1759-60.

[3] Id. at e1760.

[4] National Pesticide Information Center, Chlorpyrifos, http://npic.orst.edu/factsheets/chlorpgen.html (last visited April 13, 2017).

[5] Id.

[6] Virginia A. Rauh, ScD., Discussion of Analyses of Prenatal Chlorpyrifos Exposure and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes, Columbia School of Children’s Environmental Health, https://archive.epa.gov/scipoly/sap/meetings/web/pdf/rauh.pdf (last accessed April 13, 2007).

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] University of California Berkley, Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas (CHAMACOS), http://cerch.berkeley.edu/research-programs/chamacos-study (last visited April 13, 2017). See also Engel SM, Bradman A, Wolff MS, Rauh VA, Harley KG, Yang JH, Hoepner LA, Barr DB, Yolton K, Vedar MG, Xu Y, Hornung RW, Wetmur JG, Chen J, Holland NT, Perera FP, Whyatt RM, Lanphear BP, Eskenazi B. Prenatal Organophosphorus Pesticide Exposure and Child Neurodevelopment at 24 Months: An Analysis of Four Birth Cohorts. Environ Health Perspect. 2016 Jun;124(6):822-30. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1409474. Epub 2015 Sep 29. PubMed PMID: 26418669; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4892910. See also Engel SM, Wetmur J, Chen J, Zhu C, Barr DB, Canfield RL, Wolff MS. Prenatal exposure to organophosphates, paraoxonase 1, and cognitive development in childhood. Environ Health Perspect. 2011 Aug;119(8):1182-8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003183. Epub 2011 Apr 21. PubMed PMID: 21507778; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3237356.

[10] U.S. Environmental Protection Administration, Chlorpyrifos Acute and Steady State Dietary (Food Only) Exposure Analysis to Support Registration Review, EPA-HQ-OPP-2008-0850-0197 (Nov. 18, 2014), https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=EPA-HQ-OPP-2008-0850-0197.

[11] U.S. Dep’t of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service, Pesticide Data Program, https://www.ams.usda.gov/datasets/pdp (last visited April 13. 2017).

[12] U.S. Environmental Protection Administration, Chlorpyrifos Acute and Steady State Dietary (Food Only) Exposure Analysis to Support Registration Review, EPA-HQ-OPP-2008-0850-0197 (Nov. 18, 2014), https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=EPA-HQ-OPP-2008-0850-0197.

[13] U.S. Environmental Protection Administration, Chlorpyrifos: Revised Human Health Risk Assessment for Registration Review, EPA-HQ-OPP-2015-0653-0454 (Nov. 3, 2016), https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=EPA-HQ-OPP-2015-0653-0454.

[14] 21 U.S.C. § 346a(b)(2)(A)(ii).

[15] 21 U.S.C. § 346a(b)(2)(C).

[16] U.S. Environmental Protection Administration, Chlorpyrifos: Acute and Steady State Dietary (Food Only) Exposure Analysis to Support Registration Review, EPA-HQ-OPP-2008-0850-0197 (Nov. 18, 2014), https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=EPA-HQ-OPP-2008-0850-0197.

[17] 80 Fed. Reg. 69,080, 69,081 (Nov. 6, 2015).

[18] U.S. Environmental Protection Administration, Chlorpyrifos: Revised Human Health Risk Assessment for Registration Review, EPA-HQ-OPP-2015-0653-0454 (Nov. 3, 2016), https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=EPA-HQ-OPP-2015-0653-0454.

THEY WILL NEVER STOP UNTIL WE STOP THEM!

Dow, Monsanto, Syngenta, Bayer, Dupont, BASF

If we are going to stop this attack on our children we need to vote people supporting Chlorpyrifos/toxic poisons out of office, and use our people power to call those in political power to voice our rejection of these actions, be willing to take to the streets to make our voices be heard, and use our dollars to stop big corporate from doing this to us and our children.

WHO ELSE DOES AN UNBORN CHILD HAVE TO FIGHT FOR THEM? THEY CANNOT FIGHT FOR THEMSELVES, AND DEPEND ON US TO PROTECT THEM. These pesticide makers don't care about our children only money. We have to be willing to fight for our children and accept it is probably going to be the case for a long time because we have been sleeping at the wheel and they now have amassed great power and billions of dollars they can use to buy our government officials, place their people in key government positions, and dictate what they want.

When our children are disabled, it is not only a hardship for the family, but also for society on many levels. We miss out on new ideas and creativity when our IQ is diminished. Ideas that could create new technologies to make this a better world, leaders and productive members of society that can reach their true potential instead of being robbed and limited of their abilities.

From a public health standpoint, our systems of support are bombarded with additional financial burdens. Funding that could be used for higher education, supporting new idea development, and making our country even greater because of the brilliance of our citizens goes for other social services and disability. Limiting our children's potential is a gross act but unfortunately very real right now. Please do what you can to stop it!

When our children are disabled, it is not only a hardship for the family, but also for society on many levels. We miss out on new ideas and creativity when our IQ is diminished. Ideas that could create new technologies to make this a better world, leaders and productive members of society that can reach their true potential instead of being robbed and limited of their abilities.

From a public health standpoint, our systems of support are bombarded with additional financial burdens. Funding that could be used for higher education, supporting new idea development, and making our country even greater because of the brilliance of our citizens goes for other social services and disability. Limiting our children's potential is a gross act but unfortunately very real right now. Please do what you can to stop it!

YES YOU CAN TRUST THE ORGANIC SYMBOL

USDA Organic Certification requires a long process, inspections, and proof so don't buy into pesticide companies propaganda generated by the "Merchants of Doubt" that try and discourage you from trusting and buying these product. Grace Gurney who wrote the organic standards for the LAW said that even bad organic is much safer than conventional. It is actually not fair that the farmer that is not poisoning food, and working harder to create a safe product is burdened with the expense and work of being certified. We should instead make those using shortcuts that poison people and cause environmental damage, disease and huge healthcare expenses have that burden.

Buying ORGANIC says I refuse to eat foods containing these chemicals or any pesticides. Our top scientists keep saying, "THERE IS NO SAFE DOSE FOR POISON. PESTICIDES ARE DESIGNED TO KILL CELLS AND THAT IS WHAT IT DOES IN OUR BODY. OUR SOIL IS ALSO DEAD WITH KEY MICROORGANISMS THAT PROVIDE NUTRITION IN OUR FOOD DESTROYED! Those same organisms REVERSE CLIMATE CHANGE FASTER THAN ANYTHING ELSE WE CAN DO SO WIN-WIN. With no market we will make them go away.

Chlorphyrifos = Brain Cell Death

THE RESEARCH HAS BEEN DONE AND PROVEN!

Prenatal chlorpyrifos exposure alters

brain structure, affects IQ in children

Rauh is deputy director of the CCCEH, which receives grant funding from the NIEHS and EPA. (Photo courtesy of Columbia University)

Rauh is deputy director of the CCCEH, which receives grant funding from the NIEHS and EPA. (Photo courtesy of Columbia University)

By Carol Kelly

A new NIEHS-funded study reports that when a pregnant woman is exposed to chlorpyrifos, a commonly used pesticide, her child’s developing brain may be damaged, leading to lowered intelligence.

“The prenatal period is a vulnerable time for the developing child, and that toxic exposure during this critical period can have far-reaching effects on brain development and behavioral functioning,” said NIEHS grantee Virginia Rauh, Sc.D., a professor at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. “We have demonstrated that there is a relatively monotonic dose-response effect, suggesting that some small effects occur at even very low exposures.”

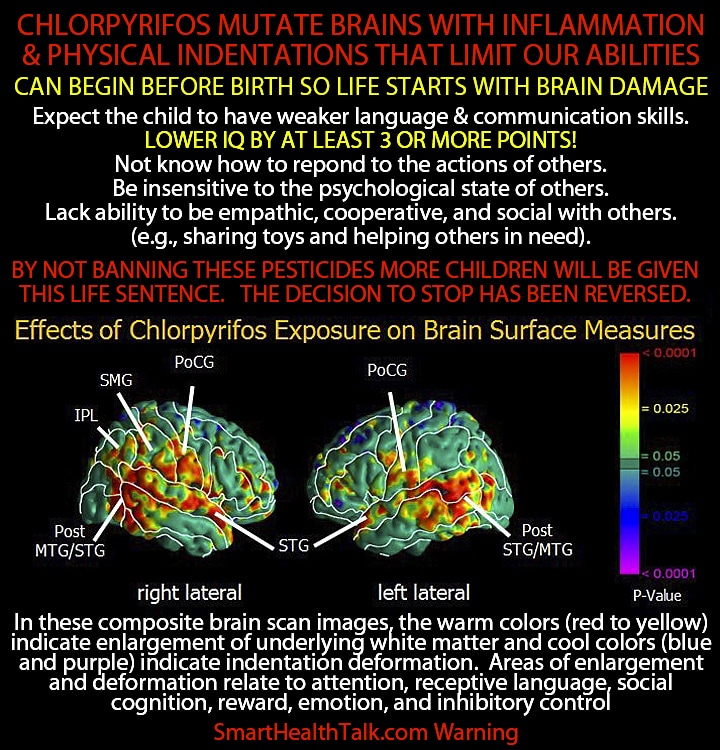

The evidence comes from researchers who conducted a recent brain imaging study of children exposed prenatally to chlorpyrifos. In addition to Columbia University scientists, the team included researchers affiliated with Duke University Medical Center, Emory University, and the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

This study is the first of its kind to use magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Digital images produced from MRI scans are quite detailed and can detect small changes within the brain.

In the scans, structural changes — abnormal areas of enlargement and indentation across the surface of the brain — appeared among the children whose mothers had been exposed to higher levels of the pesticide. In three of four brain regions, higher chlorpyrifos exposure was consistent with lower full-scale intelligence quotient (IQ) measures in the exposed children.

The brain abnormalities appeared to occur at exposure levels below the current U.S. Environmental Protection Agency threshold for toxicity, according to the researchers.

Data implications

To conduct the study, certain brain surface features of 40 urban children were examined. The sample size, although modest, nevertheless permits generalization of findings to a larger urban population, because it was a representative community-based sample.

“The group does not have exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [PAHs] or second hand smoke, two other exposures that might also have adverse effects on brain development and neurocognitive outcomes,” explained Rauh. “So, the small sample size, common in MRI studies, is balanced by a relatively pure or unconfounded design.”

Although residential application of chlorpyrifos was banned in 2001, the insecticide is still approved for other uses. Chlorpyrifos continues to be present in the environment through its extensive use in wood treatments and public spaces, such as golf courses, parks, and highway medians. People near these sources can be exposed by inhaling the chemical, which drifts on the wind. Additionally, chlorpyrifos is approved for food agriculture, and exposure can also occur by eating fruits and vegetables that have been sprayed.

“Even if dietary doses from residue on food are low, and we think they are for any one food, what happens if a person is eating five different foods on a daily basis, each with a small amount of chlorpyrifos residue?” posited Rauh. “This is something to think about.”

Future research to continue examining pesticide effects on children

“It will be important to continue to follow this cohort of children, to see if the problems resolve or whether they are irreversible, which is an outcome suggested by animal research literature,” said Rauh. “It might be possible to design an intervention to address the moderate cognitive deficits.”

“If the animal studies suggest there may be a problem, and we follow up with human work that is confirmatory, then we would be wise to limit the use of such chemicals when the evidence starts to build up,” added Rauh. “There are plenty of examples of widespread or commonly used exposures, for example, lead and tobacco, where we waited too long to try to reduce exposure, with the unfortunate result of great harm to large numbers of individuals, which might have been preventable had we paid attention to the mounting evidence.”

This research was supported by NIEHS grants for The Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health,Prenatal PAH Exposure, Epigenetic Changes, and Asthma, and Health Effects of Early-Life Exposure to Urban Pollutants in Minority Children.

Citation: Rauh VA, Perera FP, Horton MK, Whyatt RM, Bansal R, Hao X, Liu J, Barr DB, Slotkin TA, Peterson BS. 2012. Brain anomalies in children exposed prenatally to a common organophosphate pesticide. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109(20):7871-7876.

(Carol Kelly is a research and communication specialist with MDB, Inc., a contractor for the NIEHS Division of Extramural Research and Training.)

GO TO ARTICLE LINK

A new NIEHS-funded study reports that when a pregnant woman is exposed to chlorpyrifos, a commonly used pesticide, her child’s developing brain may be damaged, leading to lowered intelligence.

“The prenatal period is a vulnerable time for the developing child, and that toxic exposure during this critical period can have far-reaching effects on brain development and behavioral functioning,” said NIEHS grantee Virginia Rauh, Sc.D., a professor at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. “We have demonstrated that there is a relatively monotonic dose-response effect, suggesting that some small effects occur at even very low exposures.”

The evidence comes from researchers who conducted a recent brain imaging study of children exposed prenatally to chlorpyrifos. In addition to Columbia University scientists, the team included researchers affiliated with Duke University Medical Center, Emory University, and the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

This study is the first of its kind to use magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Digital images produced from MRI scans are quite detailed and can detect small changes within the brain.

In the scans, structural changes — abnormal areas of enlargement and indentation across the surface of the brain — appeared among the children whose mothers had been exposed to higher levels of the pesticide. In three of four brain regions, higher chlorpyrifos exposure was consistent with lower full-scale intelligence quotient (IQ) measures in the exposed children.

The brain abnormalities appeared to occur at exposure levels below the current U.S. Environmental Protection Agency threshold for toxicity, according to the researchers.

Data implications

To conduct the study, certain brain surface features of 40 urban children were examined. The sample size, although modest, nevertheless permits generalization of findings to a larger urban population, because it was a representative community-based sample.

“The group does not have exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [PAHs] or second hand smoke, two other exposures that might also have adverse effects on brain development and neurocognitive outcomes,” explained Rauh. “So, the small sample size, common in MRI studies, is balanced by a relatively pure or unconfounded design.”

Although residential application of chlorpyrifos was banned in 2001, the insecticide is still approved for other uses. Chlorpyrifos continues to be present in the environment through its extensive use in wood treatments and public spaces, such as golf courses, parks, and highway medians. People near these sources can be exposed by inhaling the chemical, which drifts on the wind. Additionally, chlorpyrifos is approved for food agriculture, and exposure can also occur by eating fruits and vegetables that have been sprayed.

“Even if dietary doses from residue on food are low, and we think they are for any one food, what happens if a person is eating five different foods on a daily basis, each with a small amount of chlorpyrifos residue?” posited Rauh. “This is something to think about.”

Future research to continue examining pesticide effects on children

“It will be important to continue to follow this cohort of children, to see if the problems resolve or whether they are irreversible, which is an outcome suggested by animal research literature,” said Rauh. “It might be possible to design an intervention to address the moderate cognitive deficits.”

“If the animal studies suggest there may be a problem, and we follow up with human work that is confirmatory, then we would be wise to limit the use of such chemicals when the evidence starts to build up,” added Rauh. “There are plenty of examples of widespread or commonly used exposures, for example, lead and tobacco, where we waited too long to try to reduce exposure, with the unfortunate result of great harm to large numbers of individuals, which might have been preventable had we paid attention to the mounting evidence.”

This research was supported by NIEHS grants for The Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health,Prenatal PAH Exposure, Epigenetic Changes, and Asthma, and Health Effects of Early-Life Exposure to Urban Pollutants in Minority Children.

Citation: Rauh VA, Perera FP, Horton MK, Whyatt RM, Bansal R, Hao X, Liu J, Barr DB, Slotkin TA, Peterson BS. 2012. Brain anomalies in children exposed prenatally to a common organophosphate pesticide. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109(20):7871-7876.

(Carol Kelly is a research and communication specialist with MDB, Inc., a contractor for the NIEHS Division of Extramural Research and Training.)

GO TO ARTICLE LINK

RSS Feed

RSS Feed