Why Controlled Fires are Healing and Protective from Forest Fire

|

Margo Robbins, Yurok Tribe

|

Smart Health Talk talked to Margo Robbins from the Yurok Tribe that have been using controlled burns for hundreds of years. Our forest fire problems started when the Federal gov't ordered these burns to be stopped in the early 1900s. They need to be brought back NOW so a 10 year plan to stop the massive fires can be developed. |

to Prevent Forest Fires

This article and video tells the story of why the Yurok Tribe have

used the Cultural Burning for hundreds of years.

GO TO ARTICLE

BY HEIDI WALTERS

When Thomas Willson was little, his grandmother would send him and his two brothers outside each fall to light fires.

"She'd give each of us a book of matches and we'd walk up to the top of the ridge then come back down, lighting fires all the way through the hazel brush," Willson recalls. "There was very little fuel, and so the fire would just creep around."

The next spring, the burned hazel would send up first-year shoots from the fire-purified ground: straight, strong, flexible sticks which, if picked before their buds leafed out, were perfect for Willson's grandmother Teresa Mitchell's baskets.

Willson, 51, reaches out to break a stem off a bushy hazel. It's mid-June, and he's standing on a forested slope just off State Route 169, a narrow, winding dead-end that departs from State Route 96 just past Weitchpec and follows the Klamath River downstream to the northwest. Though it's nearing the high 80s, the land here is still quite green because of its coastal influence; just a dozen or so miles inland, around Orleans and Somes Bar, temperatures are nudging closer to 100. A robin chortles nearby, and then a hermit thrush trills. But Willson is listening for the pigeons cooing, farther off. There's one; used to be more of them when he was a kid, he says.

Soft, early summer leafy plants, some popping with bright flowers, flood the ground at Willson's feet, but the understory is still fairly open. This spot was burned last year. Nearby in these hills are three patches of clean, black-streaked ground and shriveling young trees, burned by deliberate fires this spring. But most of this downriver land west of Weitchpec cuts through a dense overgrown jumble of towering Douglas firs, maples, oaks, madrone, hazel, pepperwood and a brushy undergrowth of saplings and other plants.

It's the same throughout most of this mountainous region, from the Klamath Mountains south to Mendocino and beyond: choked landscapes where decades of fire suppression, development and logging have created kindling forests abutting urban pockets. Limbs, downed trees and duff have piled up. And this summer, two years of drought in, the land is so tinder dry that fire managers are predicting what could be a fire season like nobody's seen.

Efforts are underway to alleviate the high fuel situation with more prescribed burns. In the meantime, communities and agencies are planning for the worst. There's tons of dry fuel in the woods, a continued drought, and a fire season on our doorstep looking like it could be a mean one. Suppression is still going to be the main tool.

"This spot was all prairie when I was a kid," Willson says. And he has a copy of a photo from the 1890s, he adds, that shows even more woods-flanked prairie sweeping from here to a town a mile or so upriver.

Willson is a commercial fisherman who also runs a guide service and rents a few cabins at his resort, Spey-Gee (Yurok for "fish hawk"), near here. This is the neighborhood where he and his brothers grew up hunting, collecting mushrooms, fishing, picking and peeling hazel sticks, mining willow roots and lighting fires for Gram.

They weren't supposed to be lighting those fires, according to the law. But they were simply doing what their people, the Yurok, had done here for centuries, treating the land with fire. Fire, applied routinely, burned at low intensity, refreshing the hazel and killing weevils that bore into it and made its stems pulpy and weak. It also burned duff and the dropped acorns infested by moth larvae, reducing the hatch of moths that would fly into the tan oak trees to lay eggs and infest more acorns. Fire killed molds and other pests that affected berries and pepperwood nuts and other plants. Fire spurred the growth of bear grass, also used in making baskets. Fire kept forests from getting choked with brush and thickets of scrawny trees, and from taking over the prairies where the elk and deer grazed. And fire made a space around Yurok homes, helping protect them from wildfires.

After the "Big Blowup" of 1910 — a two-day, multi-conflagration that burned 3 million acres across Montana, Idaho and Washington and killed 85 people — the fledgling United States Forest Service solidified its fire policy: All fires were to be stomped out, if possible. And native people were banned from conducting their traditional burns; most had stopped by the 1930s. But a few continued to do it until the 1970s, when Willson says the government cracked down on people like his grandmother.

"They said they were going to put us in jail if we didn't quit," he says. "Then they called it arson."

The land grew choked with overgrowth. The majority of tan oaks acorns became infested. Douglas firs, some planted for timber, took over prairies.

Lately, the Yurok — like other tribes in the nation, including the nearby Karuk — have been bringing back traditional burn practices, working with a mix of state and federal agencies, community groups and private organizations. Last year, the Yurok Tribe did its first official cultural burn in decades. This May and June it did more, with more planned in the future. The Karuk, likewise, have been doing official culture burns.

This return to traditional fire management is part of a larger shift happening in wildfire management, away from the full-suppression mentality and toward using prescribed fire as a way to bring the landscape back into a more fire-resilient balance. A century of suppression — a particularly wet century, at that, with massive vegetation growth — has led to tree-choked forests and massive piles of dead fuel on the land. Fires that do take hold — say in a dry year with lots of lightning — tend to grow larger and are harder to control.

Some entities are already well on top of the prescribed burning method. Redwood National Park, notably, has been regularly setting prescribed fires in the Bald Hills for more than 20 years to restore the prairies once maintained by native people. But many agencies prescribe fire on a limited basis. They want, and some plan, to do more. The idea of increasing prescribed burns is that, if enough land is burned more regularly, at a lower intensity, there will be less fuel to burn when lightning, or a human-caused spark, strikes. These fuel breaks will make wildfires sweeping in from the backcountry less threatening, and therefore backcountry wildfires won't need to be battled. They, in turn, would help achieve balance.

In January, California Gov. Jerry Brown declared a drought emergency. In some parts of the state the 2013 fire season had never really ended, and by January 2014 even normally watery, lush Humboldt had already seen a couple of fires. In mid-May, Tom Hein, chief of CAL FIRE's Humboldt-Del Norte unit, declared fire season had officially arrived.

It's typical this time of year in our northwest corner of California to have a high pressure ridge squatting off the Pacific Coast keeping us dry. What's not so typical, says National Weather Service meteorologist Alex Dodd, out at Woodley Island, is to have a high-pressure ridge hovering persistently out there in the winter. But that's what we've had, with but minor breaks, through the past two winters, he says, and it's pushed the storm-bearing jet stream far north of us. Last year ended up being the driest period on record in California. This year looks not much better.

While the rest of California is drier, here in northwestern California we're at 50 percent of our normal rainfall, says Dodd. Eureka, for instance, usually gets around 40 inches of rain in the winter; this year, it's recorded just under 21 inches. Up in Crescent City, the winter rains brought just 32 inches, far short of the typical 63 inches. Dead fuels — downed trees and large limbs, which burn hot and slow — are at near-record dry levels, says Dodd. Live fuels — living plants, spring growth — are still green, but beginning to dry out. Talk of an El Niño winter is only semi-promising, because it's uncertain yet if the event will be strong enough to bring wet storms to Northern California, says Dodd. But even if it shapes up to be a strong one, El Niño only affects the winter pattern, not the summer. Right now, there's no rain in sight.

David Markin, fire suppression chief for Six Rivers National Forest's Orleans/Ukonom Ranger District, says it's the driest June he's seen in his 26 fire seasons with the district.

As summer progresses, it's likely only to get drier. Large, hard-to-control fires are the portent.

In a letter to personnel in various agencies and community organizations, Klamath National Forest Supervisor Patty Grantham wrote that "most people realize we are in a drought, but I'm not sure how many realize how really serious it is with respect to wildfire potential."

"If current trends continue," she added, "we may see conditions in Siskiyou County that no one living has ever seen. Makes you stop and think, right?"

The Klamath forest is east of the Six Rivers National Forest and north of the Shasta-Trinity; the three meet in the mountains east of Willow Creek and the Hoopa Valley. Grantham urged the recipients of her letter to get the word out to people to "be vigilant and ready for lightning" and especially vigilant about human-caused fires.

"As the saying goes, there is zero risk to homes, firefighters, citizens, natural resources, communities, etc., from the fire that never starts," she wrote.

Agencies such as CAL FIRE and its associated community fire safe councils, Six Rivers National Forest, the Bureau of Land Management and local volunteer fire departments are issuing instructions on how to deal with the drought and fire conditions. In the Six Rivers National Forest, for instance, special fire restrictions went into place June 16 to try to reduce human-caused fires. They limit campfires to designated fire safe sites (with a permit) and developed recreation sites (no permit needed); limit smoking to enclosed vehicles, buildings and the aforementioned sites; prohibit the use of internal combustion engines except on National Forest System roads or designated trails; prohibit the use of explosives; and require a campfire permit for certain activities such as using lanterns or portable stoves using gas, jellied petroleum or pressurized liquid.

CAL FIRE, meanwhile, has hired 125 more firefighters, including 10 for the Humboldt area. And it is working closely with other agencies, including federal forest managers, to coordinate wildfire responses. CAL FIRE spokesperson Scott McLean says burning is banned in the summer within the 31 million acres of private land it takes care of. He adds if you're planning to clear debris around your property, do it in the morning before 10 a.m. while there's still moisture in the air, and be careful with equipment that could throw a spark. If you have to mow, use a nylon-twine mower. Don't drive onto dry grass: Your catalytic converter is hot and could ignite it. And if you're towing, make sure your chain doesn't drag and cast sparks.

Meanwhile, the Humboldt County Sheriff's Office is busy rewriting its emergency response plans to be more ready for wildfires. It's not a typical duty, but last year the sheriff ended up sending 12 officers to help close roads (including State Route 96) and evacuate residences when a human-caused fire in Orleans grew rapidly out of control.

"Late in the evening they sent calls to Arcata police, Humboldt State University police, Eureka police and the Sheriffs' Office to send officers," said Sheriff's Lt. Steve Knight. "All responded lights-and-sirens to assist with the evacuations because at that point life and safety were threatened."

This season, the Sheriff's Office is re-training its officers on how to deal with wildfire responses, including how not to become victims themselves. It's also planning to assign an officer to coordinate with fire personnel from the start, and it's preparing for the possible use of the reverse 911 system to help alert people.

Dan Kelleher, a "burn boss" with Firestorm, a company that trains and also hires out fire management crews, has been in the fire business for 35 years. He's trained folks all over the country how to fight fires and use prescribed fire to protect landscapes. He spent 150 days in Yosemite in 2005-2006 helping the park with its prescribed burning program — and anybody griping about how huge that Rim Fire got last year might want to at least acknowledge how it settled down once it reached a prescribed-fire area, he says.

"Anybody who does not see prescribed fire as a way to get the earth back to where she needs to be is just not looking hard enough," Kelleher says.

Just about everyone agrees, says Zack Taylor, the fuels chief for Six Rivers National Forest. Last fall, in fact, Six Rivers did one of its biggest prescribed burns in a long time, 260 acres of choked understory near Orleans.

But there's still not that much good fire, overall, getting on the ground.

The trouble has been that prescription burns require not only the right weather conditions — it can't be too dry or too wet — but they also require resources, including crews to do the work, and money to buy equipment. Prescription burns also are subject to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and require a permit — which takes a long time, money, and a slew of specialists, including wildlife biologists, fisheries biologists, soil scientists and archeologists to prepare each application. As well, the would-be firebugs have to convince the public that some smoke is good smoke.

CAL FIRE's McLean says a $152 fee — instituted two years ago and levied on landowners in the agency's state responsibility areas — will help enable it to do more prescribed burns to protect communities.

Public entities such as CAL FIRE and the U.S. Forest Service also are forging partnerships with private groups to jointly shoulder the cost and further the goal of introducing more prescribed fire to landscapes. In Northern California, CAL FIRE and its fire safe councils, the Forest Service, Department of the Interior agencies, tribes, community groups and Firestorm have been participating in workshops and fire training exchange programs organized by the Northern California Prescribed Fire Council. The council is a collaboration of these entities plus others, including university researchers. It holds two annual regional meetings, works on policy and education and hosts trainings such as one held last fall in Orleans and other North Coast communities. That training exchange was funded by yet another entity, the Fire Learning Network, a partnership between federal land management agencies and The Nature Conservancy. The Fire Learning Network helps conducts training exchanges around the country to speed up the restoration of good fire to grasslands, forests and other landscapes and create "fire-adapted communities." In these training exchanges, firefighters, would-be firefighters and others come from all over the country, and sometimes from other countries, to earn a certification or improve their skills, all while helping a community do some good burning and learn about becoming fire-adapted. The network also has eight pilot communities in the country that it's helping — financially and technically — to further develop techniques and plans for creating fire-adapted communities.

One of these pilot communities is the Orleans/Somes Bar area, which has already proved to be a model for how to work with agencies to become fire-safe. Its fire safe council has aimed to restore a traditional fire regime ever since it formed, in 2001, following a big fire in Orleans.

In the training exchange organized last fall by the Northern California Prescribed Fire Council, participants burned around 500 acres total, including areas in Orleans, the Bald Hills, Hayfork and Whiskeytown. Taking part in it were people from the Karuk Tribe, the Orleans/Somes Bar Fire Safe Council and other fire safe councils, the Mid-Klamath Watershed Council and the Forest Service. There will be another training exchange this fall just around Orleans, which will include some cultural burns to produce better grass and acorns.

Members of this regional group also are collaborating on a landscape-wide fire-management strategy for a 1.2 million acre region between Orleans and Bluff Creek up to Seiad Valley, in Siskiyou County, and including the Salmon River and some of the Klamath. The plan, says Will Harling, with the Orleans/Somes Bar Fire Safe Council and Mid-Klamath Watershed Council, looks at where and how often fires have occurred across this region, determines how much fire might have happened in these areas if fires hadn't been suppressed, and devises prescribed-fire treatments suited to restore that old balance.

Almost 50 percent of these 1.2 million acres, notes Harling, hasn't seen fire in more than 100 years. Some of this vegetation-choked land is near communities. The plan, says Harling, is to do more of the work local fire safe councils have already started: thinning, burning, clearing space around structures and roads, and adding more escape routes.

"The Orleans Fire [last year] bumped up against some of our fuel treatments, a place where we'd recently been brushing and prescribed burning," says Harling. "So that was effective."

The all-encompassing, stakeholder-collaborated plan for that 1.2 million acres, meanwhile, will make the NEPA permitting process go faster, should the group get a big chunk of money to implement it.

"Once we get our fuel breaks in place, and the community feels confident, then the forest service will have the leeway to let wildfires burn," says Harling. "That will be when we've arrived."

Until then, they're pecking away at fire-safing the land and their communities. Locals are still jumping into the fray during wildfires, donning their own gear to show the non-local fire crews — a new batch every two weeks — where the best places are to put fuel breaks. And the bureaucratic gains are increasing. Bill Tripp, the Karuk Tribe's eco-cultural restoration specialist, says the tribe is getting closer to being able to once again roll burning logs down Offield Mountain — an act that was part of the tribe's annual world renewal ceremonies up until 103 years ago.

"It signified singeing our Mother's hair — Mother Mountain — so she could mourn for all of those [who passed] during the year," says Tripp. It was symbolic, he adds, but it also had a functional purpose: putting good fire on the land to help grow fresh medicines, food and weaving fibers.

After cultural burning was banned, in 1911, says Tripp, those who continued to do it were called "incendiary burners" and, sometimes, were shot for it.

"There's still a lot of tribal tension in communities over it," he says.

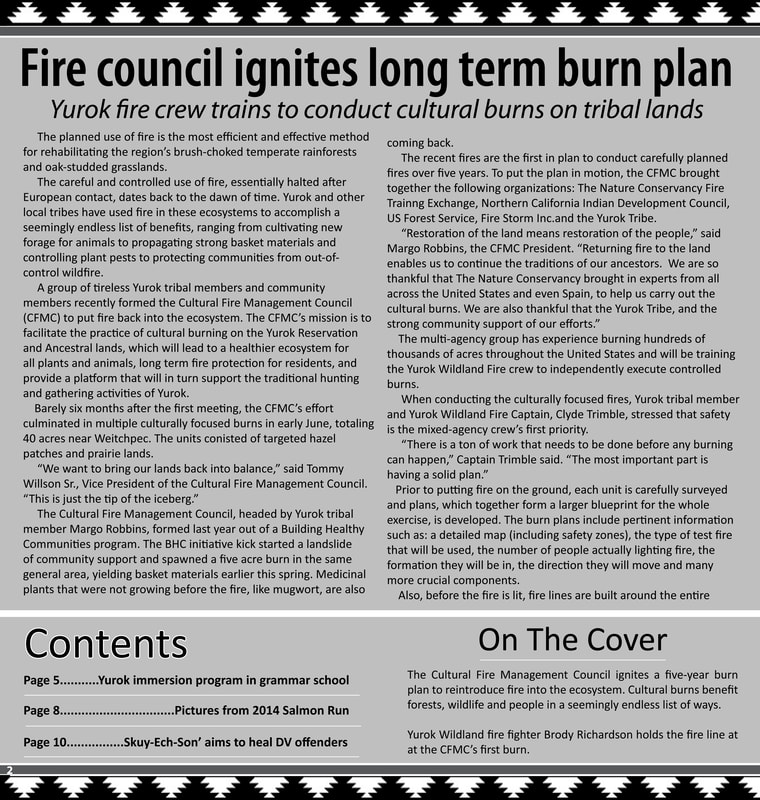

Two years ago, Margo Robbins, 52, wanted to weave a traditional Yurok basket for her new grandbaby. She studied the one her own grandmother Minnie Reed, a renowned basket weaver, had made, and realized she didn't have enough hazel sticks. She needed 75 4-foot stocks for the frame. She searched downriver but couldn't find any because there was no place where the hazel had been burned.

"I had to buy sticks," she says.

This spring, however, she was able to pick good sticks for her weaving — strong, flexible young stems, shooting straight from ground burned last year in a prescribed fire the tribe and CAL FIRE crews set. And there should be even more sticks in time — and more acorns, bear grass, open prairie and so on — if the Yurok Tribe's fledgling cultural burn program grows.

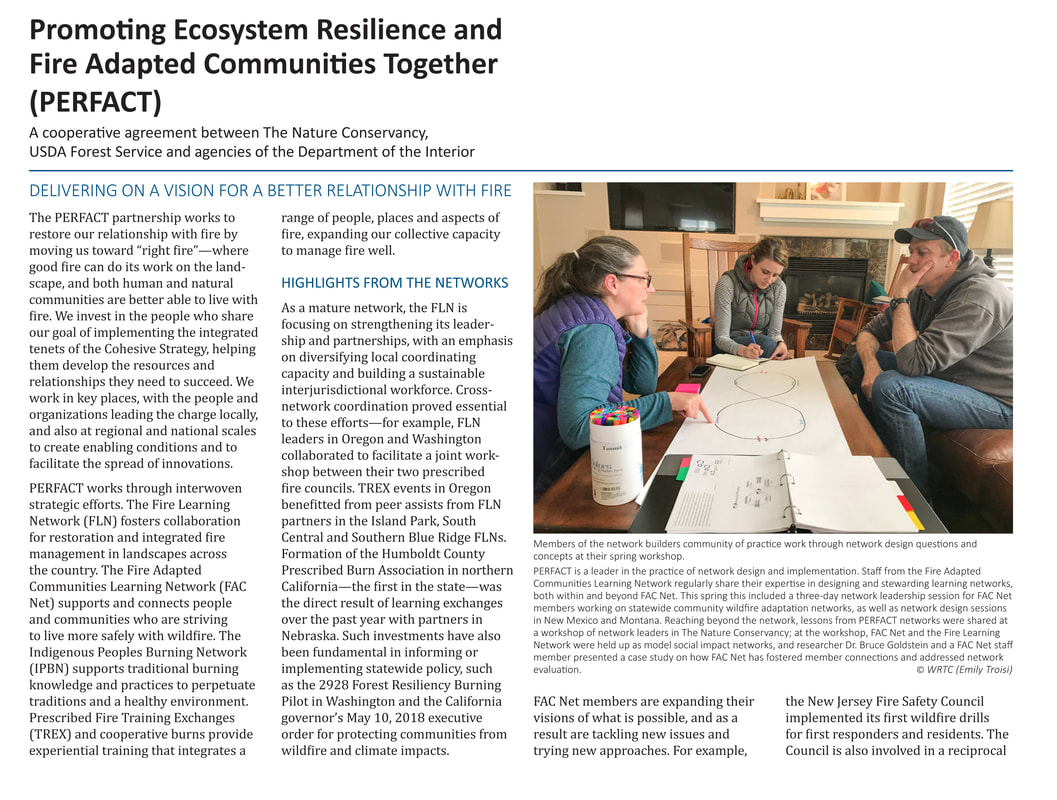

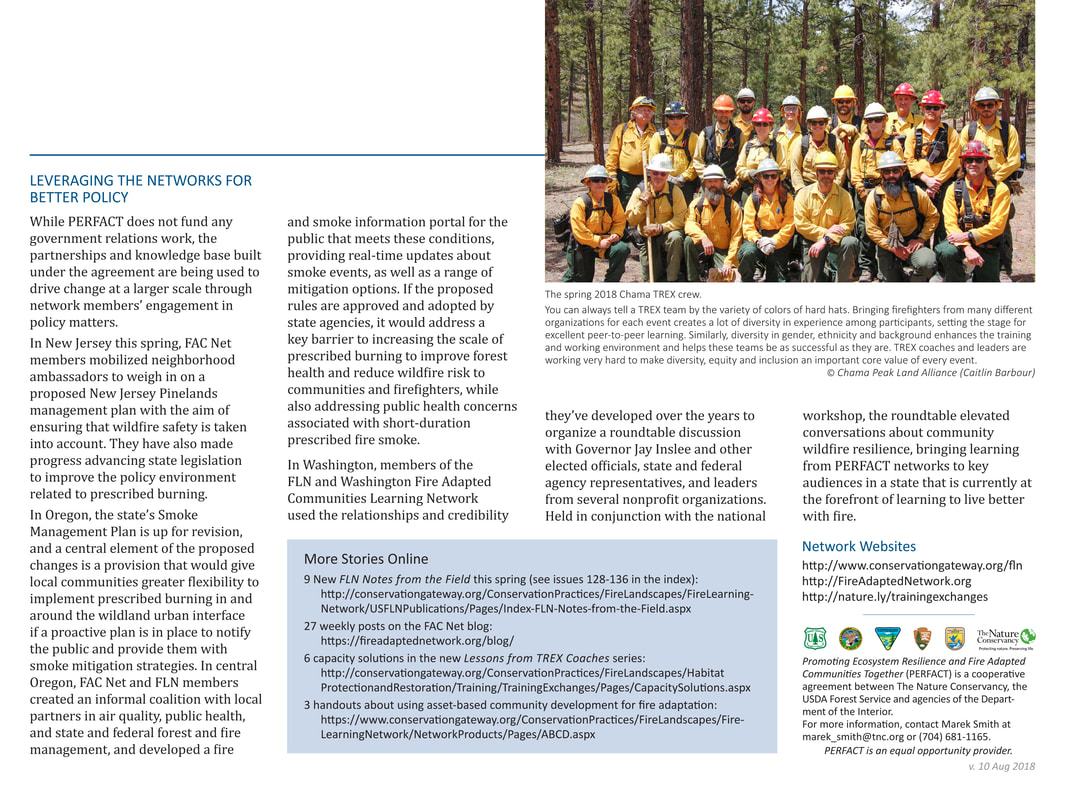

After last year's work, the tribe formed a new committee that's much like a fire safe council but places special emphasis on cultural burning. The Yurok Cultural Fire Management Council, of which Robbins is president, is now involved with The Nature Conservancy's Fire Learning Network, and this spring hosted a training exchange that burned around 50 acres in Tom Willson's neighborhood (including some of his land). Kelleher, the burn boss, was there along with six others from Firestorm, as well as folks from CAL FIRE, Forest Service districts in Oregon, Utah and New Mexico, Spain's Ministry of Forestry (really!), and 11 from the Yurok Tribe. Five Yurok trainees ended up with firefighting jobs with Firestorm, including Willson's 21-year-old son, Thomas Willson Jr.

Willson, who is vice president of the cultural fire management council, says the tribe gets to work with the Nature Conservancy another four years. He expects they'll double the amount of acreage burned each year in subsequent training exchanges. After that, Willson and Robbins agree, it would be nice if the council evolved into a nonprofit that could better spread the knowledge of prescribed burning, especially for traditional purposes, throughout the community and to young people.

"We actually want our kids to take ownership of our lands," says Willson. "Once they have ownership, they'll care about it."

And maybe the tribe will someday take sovereign control of its own burn permitting, currently controlled by CAL FIRE.

For Willson, who wasted most of his young adulthood on drinking and drugs until his grandmother helped him get sober, this has become his most important work.

"The Creator put me here to take care of these lands, and if I don't take care of them I don't know what I'm going to tell the Creator when I get to him," he says. "I'm supposed to make things better in my lifetime for the next seven generations."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed